1943

Disembarking on 18 December 1942 we travelled by train from Gourock to Harrogate Personnel Dispersal Centre and were billeted in the Queen's Hotel. We soon found out that some high-spirited new aircrew had earned themselves an unenviable reputation in Harrogate and that a Squadron Leader Fairey had been drafted in to restore discipline. If you did anything wrong, you were liable to be sent to a former Butlin's holiday camp at Filey on a 'battle course', part of which involved crawling in the mud through obstacles while live rounds were fired over your head.

On my first early morning parade I found S/L Fairey glowering at me and wondered why. 'Are you in the Royal Canadian Air Force?' he inquired. 'Well, no,' I said. 'In that case,' he said menacingly, 'why are you wearing RCAF buttons?' He wasn't interested in my explanation and informed me that if I did not have RAF buttons by the following day I'd be off to Filey.

I was all round Harrogate that day trying to buy some RAF brass buttons, eventually finding a shop which stocked them. I cut off the Canadian buttons and sewed on the correct ones in time for the following morning's parade. Fairey seemed quite disappointed when he discovered I had managed to change them.

Clearly, they didn't quite know what to do with us at Harrogate apart from marching us round the place every so often, so we were given a long Christmas leave. On January 6 I received a telegram posting me to Number 7 Elementary Flying School at Desford, near Leicester - in fact to a satellite aerodrome at nearby Braunstone. I and three or four others, all qualified pilots complete with wings and commissions, found ourselves back on Tiger Moths!

The reason, we discovered, was that pilots trained overseas - where the weather was mainly clear and sunny and there were few roads and railway lines - had been returning to Britain, taking off in Hurricanes, Spitfires etc, promptly getting lost and, out of fuel, force-landing, crashing or baling out. Flying conditions in Britain, especially in winter, were far more difficult than in Canada or America.

Why roads and railway lines? Overseas, they were few and far between. If you were lost but found a main road or railway line you could soon pin-point your position. In Britain there were so many that you didn't know which one you had found.

The powers-that-be decided that overseas-trained pilots needed a dose of flying in Britain's tricky weather conditions and that if you were going to wreck an aeroplane through becoming lost Tiger Moths were cheaper!

There were other problems, such as camouflaged airfields. In fact, Braunstone was only a grass field, made even more difficult to find because it had dummy black hedges painted across it. From the air it seemed to be just a few little fields, far too small to land even a Tiger Moth.

I discovered this problem on my first 'circuit and bump' with an instructor. 'Right,' he said. 'Just take off, do a circuit and land.'

I took off, climbed away, did a 180 degrees climbing turn to 1,000 feet and flew back parallel to the take-off direction and looked out for where to turn in to descend and land. There was a difficulty - I couldn't find the aerodrome. Beaming away in the back seat, the instructor inquired why I was not getting on with the landing. 'Because I've lost the aerodrome,' I said. He swung the Moth round 180 degrees, put the nose down and said, 'There - it's straight in front of you.' So it was.

It was a salutary lesson in map reading and dead-reckoning navigation. Not long after this we were intrigued to see a Spitfire coming in to land. It was far too high and fast and when it touched down it ran across what remained of the field and ended nose down in a hedge. Out of it climbed an unhappy-looking female ferry pilot who had held off over a dummy hedge and so hurtled into the real one.

We learned more about navigation in Britain by going on cross-country flights and also did a spot of night flying, landing by the flickering light from goose-neck flares marking out the runway.

After notching up 30½ hours Tiger Moth flying it was back to the Queen's Hotel at Harrogate for more time-wasting and idleness before, on 12 March 1943, being posted to a Dispersal Depot at Bournemouth for a further month of route marches, cross-country runs and heel-cooling, interspersed by a few games of golf, visits to the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra and to afternoon tea at Beale's department store, where three elderly ladies entertained with violin music.

At last, on April 20, another posting - to 5 Advanced Flying Unit at Tern Hill, Shropshire, to fly Miles Master aircraft - just one step down from Hurricanes and Spitfires. It was here that I received another valuable flying lesson by watching Spitfire test pilot Alex Henshaw. He put on a low-level incredible acrobatic performance in a Mark V Spitfire, ending it by flying along the runway 15 feet up - and upside down! We all realised we still had a lot to learn.

I was to stay at Ternhill, flying Master 1s and 11s, for a month.

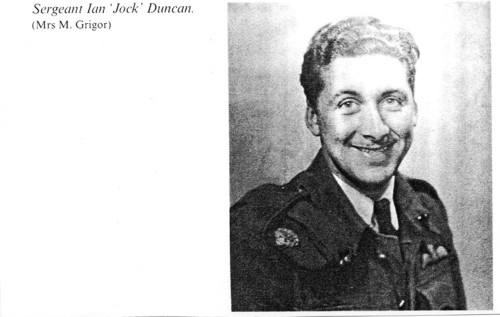

Towards the end of April I found that Ian Duncan was not far away, at 61 Operational Training Unit, Rednall, flying Spitfires.

We met at a pub near Shrewsbury railway station, where he introduced me to a very potent Scottish mixture, 'chasers' - a whisky chased down by a pint of ale. It was the last time I was to see

Ian, although, in strange circumstances, I was to meet his family on 12 July.

Ian joined 64 Squadron, flying Spitfires, was promoted to Flight Sergeant, flew on a total of 84 operations including nine at the time of the invasion, but was killed on 16 June 1944 when, having been hit by flak, he crashed into a farmhouse near St Lo.

Ian is buried in Bayeux War Cemetery, near Calvados.

Ian often flew 'The Darlington Spitfire' - paid for by the Durham town of Darlington - and is featured in a book of that name by Peter Caygill. He is described as being 'resolute, dependable and cheerful.' His sister, Margaret, asked him what it was like to fly Spitfires. His reply, 'Just like riding a bike - except that you don't have to pedal!'

Brother Tom, having gained his air gunner brevet and promotion to sergeant in September 1942, was 'crewed up' on a Halifax at Marston Moor, Yorkshire, and posted to 158 Halifax Squadron at Eastmoor, Yorkshire. His pilot: 22-year-old Canadian Nick Smith.

It was the height of the bombing campaign. Casualties were high. In fact, the Squadron lost a total of 581 aircrew - the Squadron number reversed. Coming back from one raid, badly damaged and lost, the order to bale out was given. Tom swung his turret, put out his feet and was ready to go when the bale out was cancelled. Nick had spotted the airfield and managed to land. Tom discovered that his flying boots had 'flown' away in the slipstream. This was 'carelessness' so they wouldn't give him another pair. He refused to buy them so flew from then on in his old airman's boots!

Tom completed his tour of 30 operations by 29 April, was recommended for the Distinguished Flying Medal and a commission, decided it was time to be married to fiancée Eleanor Walton, and they agreed his 22nd birthday, 15 May 1943, as the date, at Christ Church, Princess Road.

The photographs: Ian, copied from 'The Darlington Spitfire';

Tom as a sergeant air gunner; a Halifax;

me (in my Canadian uniform, complete with RAF buttons) and Mum at Thorneycroft Avenue, C-c-H.

Last pic: me leaning into a Lysander cockpit while taking a cockpit photograph.

After the wedding ceremony, at which I was best man, a reception was held at the Co-op in Chorltonville and photographs taken. Chief bridesmaid was Eleanor's cousin Joan and cousin Margaret Collier was a bridesmaid. Young brother Walter was in South Africa, training as a pilot.

Although they hadn't arranged anywhere to stay Tom and Eleanor decided to honeymoon in Morecambe, so after they had changed into 'civvies', we all dashed, rather late, for a train. Seeing the confetti on Joan and me a kindly porter cleared a way through the crowd to the platform and the train and pushed the two of us on board! There were hasty explanations and the bride and groom managed to change places with us.

At Morecambe, Tom and Eleanor found accommodation in a boarding house and had a happy honeymoon, part of it (see pix) rowing about in a boat. Well, Tom rowed and Eleanor basked in the back of the boat.

Back at the Squadron Tom was told another crew had lost a couple of members so he and another air gunner crew mate, Ted Smith, also tour completed, were asked to go on more raids in a Halifax piloted by 'Bluey' Mottershead. Like chumps, they agreed, Tom not telling anyone at home and certainly not Eleanor. Tom and Ted did five more ops and then were given leave, each soon being commissioned and both receiving their DFMs from King George V at Buckingham Palace, Tom's being presented on 1

May 1944 with Mum being present. Dad and Eleanor's mother, waited outside.

By this time he had been based for some months at Lossiemouth as a gunnery instructor.

I was at Tern Hill until 24 May when I was posted to 58 Operational Training Unit at Grangemouth, a Spitfire OTU. After various briefings, on 31 May I was told to get into a Mark 11 Spitfire and take it off. There was no room for an instructor - you were on your own.

Despite having been told about its handling qualities and speed I was

still amazed at the way the Spitfire accelerated, at its instant

response to the controls and its rate of climb. Flying it was sheer

pleasure. However, then came the problem of landing. I made a curving

approach - you had to curve it in to be able to see the runway which

would otherwise have been blocked off by the long nose - and held off to touch down. I then learned that Spitfires lose speed very slowly. I was too fast and was eating up the runway. It meant opening the throttle and going round again for another attempt, and this time made a decent landing.

At foot of page, the Grangemouth course photograph. I'm third from right, middle row.

58 OTU Grangemouth, May 1943

L to R - Back row: Sergents Morgan, Hollis, Reid, Livesly, Connell, Blair, Williams.

Middle: Sergents Farquer, Feasby, P/O Bliss, F/O Matthews, F/O Collins, P/O N Edwards P/O Brown, Sgt Graybeith.

Front: F/O Cain, P/O Laws, F/Lt Wilson, F/Lt Young, P/O Tough, P/O Gillon, P/O Tickner.

Have listed the Grangemouth group names on back of the photograph. Some of these are mentioned later in this account.

At Grangemouth we were billeted out with local families. I was lucky enough to be with a Mr and Mrs Wilkie, who made me very welcome and introduced me to Scottish customs, such as family gatherings on Sundays, rounded off by singing hymns and ditties such as 'Trees' round the piano.

During the next two weeks I enjoyed finding out more about the wonders of the Spitfire, its speed and responsiveness - and the beauty of the Scottish scenery as I flew over Loch Lomond and surrounding hills and countryside. I was also learning lessons which were to stand me in good stead later.

On one flight, during which I was due to practice radio direction finding, I certainly discovered how important it was. Flying over the top of a layer of lovely white cloud towards Stirling I saw a hole in the clouds and decided to dive through it to a lower level. I thought I was over flat countryside. I wasn't. As I pulled out of the dive I found myself heading at high speed straight towards a mountainside. Heart in mouth, I skimmed its surface. I could see the heather blowing in my slipstream. Fortunately, I missed hitting the hillside by a whisker and shot back up into the clouds.

I tried to climb out of the clouds but didn't seem able to reach their tops, so flew straight and level for a bit to re-set my gyro instruments, which had toppled, and thought I had better get a course to steer back to Grangemouth.

Still in cloud, I transmitted on the radio so that three ground stations could get a 'fix'. I was given a course to steer to Grangemouth. I set the course on the compass. After five minutes they asked me to transmit again and then said: 'Are you steering an accurate course?' Well, I had been a degree or two one one side or the other so I said: 'Certainly.' I then discovered I had set the compass red on blue - in other words, the wrong way round. I was steering away from Grangemouth, not towards it. I hastily put matters right and got back to the aerodrome. I never made this mistake again.

Some people, no doubt also in a bit of a state at the time, made this boob in Burma - and eventually came down, out of fuel, in China.

Then came 17 June when I had reached about ten hours on Spitfires, an instructor by the name of Pilot Officer R. de Burgh briefed me and Sergeant Hollis to go up with him on formation flying. We didn't know that he intended to turn this into formation aerobatics. The result was catastrophic.

For about 80 minutes, we-carried out simple exercises, mainly flying in V formation with De Burgh leading. Sergeant Hollis as Number 2 on his right and me as Number 3 on his left.

In a report I made at the time I said that at about 12.40pm De Burgh signalled that we should go into line astern. I took up my position in the rear and Sergeant Hollis dropped back but he did not come entirely into line, being still out to the right.

I gathered, from the fact that De Burgh increased speed in a dive, he was going to perform some aerobatic. I dropped back a little. Sergeant Hollis positioned himself in the middle but still out to the right.

De Burgh pulled up to start a loop and Sergeant Hollis and I followed. Sergeant Hollis went out even farther to the right and I lost sight of him. As I came over the top of the loop there was no sign of Hollis but I could see De Burgh straightening out ahead.

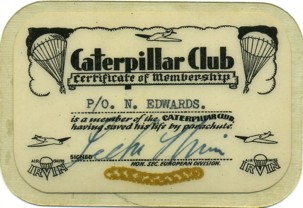

I had just finished pulling out of my dive when my plane shook violently and went into a spin. I tried to kick on opposite rudder to stop the spin but could not move the pedal. I then noticed that my port wing had been broken off and the cockpit hood had vanished. I baled out and pulled the ripcord almost immediately. The parachute opened right away. I did not know I had collided with Sergeant Hollis until later.

That was the brief report.

The wings of a Spitfire are very thin, compared with Harvards, Masters and even Hurricanes and my first thought when I saw the wing torn in half was that it had failed because of the high G - gravity force - when pulling hard out of a high-speed dive. I did not know at the time that my tail had also been broken off, which was why the rudder wouldn't work.

I don't know how long it took me to realise that I might as well try the parachute - probably only seconds but things were certainly happening fast.

I floated down into a farmer's field, near Alloa. The remains of my Spitfire crashed into the same field, not far away, and caught fire. The farmer appeared, running across the field towards the Spitfire with me shouting, 'I'm all right - over here!'

He took me into his farmhouse where his wife kindly made me a cup of the sweetest tea I've ever tasted. Must have put a week's ration in the cup.

Then he said, 'What happened to the other Spitfire?' 'What other Spitfire?' I asked. 'You were in a collision,' he said. I realised it must have been Sergeant Hollis's aircraft.

It didn't seem long before a team turned up from Grangemouth to pick me up. They took me to the place, not far away, where Sergeant Hollis had crashed, still in his aircraft. He was dead - and I felt terrible.

For the next four days I was very stiff and it was hard to sleep. The Wilkies were splendid. Then, on 22 June, I went up again for 70 minutes of local flying and the same again on the following day plus solo aerobatics. I made myself do a couple of loops, then, on subsequent days, tackled height climbs and, on 27 June, again did formation flying and moved on to tail-chases etc.

Pilot Officer De Burgh had to face a court martial, which found that there had been laxity in instructional standards.

By July 11, the course at Grangemouth completed, we moved to an airfield at Balado Bridge, near Kinross, for Squadron and Battle formation flying, air firing with camera guns - and with live ammunition on a ground target - cloud and night flying.

That was the day when, in an amazing way, I met Ian Duncan's family.

We were transported from Grangemouth to Balado in the back of a three-ton truck which broke down in a lonely country lane, apparently miles from anywhere. We sat in the truck while the driver tried to repair it. Then one of the sergeant pilots got out to stretch his legs, walked round the corner, found a small cottage, knocked on the door and asked if he could have a cup of tea. The lady who answered the door invited him in and, while making the tea, asked him if he knew of a Pilot Officer Norman Edwards. 'There a chap of that name sitting in the truck,' he said. She came out and spoke to me. This was Ian's mother!

While at Balado, until the end of July, I was a welcome visitor at the cottage, named Parkneuk, meeting Ian's father - a former policeman in Glasgow who became a gamekeeper - and their three daughters, Margaret, Joan and Anne. Margaret, then aged 15, was the oldest of the girls.

There was also always a warm welcome at Parkneuk when, after the war, I got a job with the Sunday Dispatch in Glasgow - and joined a gliding club which operated from the former RAF Balado airfield and nearby Bishop's Hill.

By then Mrs Duncan had died, Mr Duncan had re-married. The girls were still there. I attended Margaret's wedding to an ex-RAF airman Hector Smith. They had two boys, Ian - named after his uncle - and Alistair. Ian followed in his uncle's 'footsteps', joined the RAF, flew Jaguar jets, then became a commercial pilot, first with Air 2000 flying from Manchester and then Virgin, piloting Boeing 747 jumbo jets. He lives at Whaley Bridge.

Alistair went into education and married in 1999.

However, Margaret and Hector were divorced. In due course Margaret married Jim Grigor and moved to Perth. At the time of writing we are still in touch.

Returning to RAF career, at the beginning of September I was posted to West Kirby, on the Wirral, to collect overseas kit ready for departure to tropical climes. It was dreadful stuff, probably souvenirs of the Boer war. Then on 11 September it was off to Glasgow to board the 'Mooltan' for the voyage through the Mediterranean to India.

We were the second convoy to go through the Med.

The Med weather was diabolical, with heavy grey seas heaving up and down.

Nothing like the 'blue Mediterranean' that we had been told about.

The 'Mooltan' pitched and rolled and put its bows down so far that we thought it would head straight under.

Very few appeared in the dining room!

On board the 'Mooltan' were four Grangemouth course pilots:

Canadians Doug Gillon and George Brown; Andy Tough, from Aberdeen, and 'Jock' Dalrymple, who were also to join 155 Squadron. Another pilot on board, Albert 'Witt' Wittridge, also destined for 155, as was a Flight Lieutenant Meredith. He was an obnoxious character, disliked by a lot of people on board - including me - so it was with dismay when I joined the Squadron I found he was my Flight Commander.

However, in due course Meredith was to put up what we knew in the RAF as 'a fearsome black' while driving a jeep, as a result of which several pilot passengers - again including me - were injured. The end result: he was posted from the Squadron in disgrace.

As well as thousands of servicemen and women, the 'Mooltan' was carrying King Peter of Yugoslavia, complete with his very decorative entourage of ladies. They got off at Port Said. Think he was hoping to get back into Yugoslavia but Tito didn't want him.

Then it was through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea and on to Bombay, where we disembarked on 12 October, and went to nearby Worli Reception Depot.

By this time I had been promoted to Flying Officer, which meant that I was qualified to act as escort officer - guard in other words - to an Indian Flying Officer named Dabu who was under close arrest for fiddling. On 15 October I was detailed to watch him in a small building near Bombay to make sure he didn't run away. I said, 'Make sure I'm relieved tomorrow morning - it's my 21st birthday and a party has been arranged.' 'Right,' they said.

October 16 dawned. I awaited the relieving officer. He didn't turn up. I wasn't pleased.

Dabu had spent most of the previous day telling me that he was married and lived just a short walk away. Would I let him see his wife? Not likely!

However, when I was not relieved on my 21st birthday I felt a bit more sympathetic and agreed to let him pay his wife a visit. I went into a village, pottered about, looked in at a native cinema, and got increasingly worried that he might have scarpered. I rushed back to his house, he appeared immediately, looking quite happy!

At first, the days at Worli passed pleasantly enough, getting used to the heat, buying better-fitting tropical khaki, swimming at the Willingdon Club pool, ambling round Bombay and being amazed by its contrasts, ranging from wealth and luxury to absolutely abject poverty. The cinemas were marvellous, not necessarily because of the quality of the films but because of the splendid, air conditioning, cool oases from the heat. However, as time continued to go by it began to become quite boring, especially when another pilot, Flying Officer Tibbets - with whom I had become friendly - did move on to the next stage, flying at Poona, in November. My next encounter with Tibbets was very sad.

Finally, at the beginning of December 1943 I also moved on to Poona to spend a month's 'refresher' course on Harvards.

Interestingly, at that time Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi were in jail at Poona, having been accused of fomenting trouble. They were being kept out of the way for a while. Nehru was, of course, to become India's first Prime Minister after Independence and Partition (into India and Pakistan) in 1947.

Gandhi was assassinated in 1948 by a Hindu nationalist in the violence that followed Partition.