1943-1944

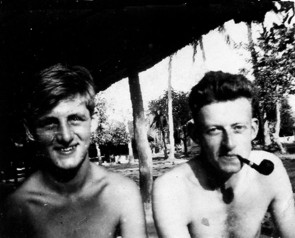

On the left hand side, a couple of photographs from early Worii days in India. At the top: Canadians Doug Gillon and George Brown; underneath: me and Doug, both friends from Grangemouth days. Together with Andy Tough and Jock Dalrymple, we were all to join 155 Squadron.

Doug, cheerful and popular, was to put up what we called 'a black', damaging his Spitfire on landing. It was judged to be blameworthy so he was posted from the Squadron - to become, would you believe, a test pilot at a maintenance unit, flying Spitfires, Hurricanes and other types! He was keen to rejoin the Squadron and eventually did so.

Happy-go-lucky and cheerful George was to die during March when, taking part in a Wing scramble, his aircraft went into a vertical dive from 23,000 feet and he did not pull out. The main theory was that he might have been suffering from a failure of the oxygen system and had probably become unconscious.

However, returning chronologically to Poona days, I was there during most of December 1943 practising instrument flying, aerobatics, map-reading, formation flying and cine-gun shooting, on Harvards, and also got a few hours in on Hurricanes. They seemed big and clumsy compared with Spitfires!

The photographs on the right-hand side are the only ones I know of taken at Poona. The top two were taken by my pilot passenger from the rear seat. The third was taken by me of the passenger, although how I managed to point the camera backwards I don't know.

I note from my diary that on 11 December, a blazing hot day, played football for the transiting officers against an Indian team. They didn't bother to wear boots! I also note that I scored.

After celebrating Christmas and New Year, a group of us set off on 1

January to join 155 Squadron at Calcutta. It was a long journey,

changing trains twice, stopping at railway stations for meals. At one

point I was invited to ride on the engine. The heat of the sun combined

with the heat from the coal fire was practically unbearable. I was glad

to get back into a carriage when we reached the next station. How the

driver and fireman coped I don't know.

We reached Calcutta around mid-day on 5 January and were taken by truck to an aerodrome at Alipore on the outskirts of the city. There we saw a lovely line-up of Mark VIII Spitfires. That's me in one (bottom pic). 155 had been flying American-built Mohawks from the Imphal Valley on the Burma border but had come to Calcutta to change them for the Spitfires.

We discovered that we were joining one of the tallest Squadrons in India. A Flight Lieutenant Ford topped the height list at six foot seven inches. The CO, Squadron Leader Winton, was a mere six-footer.

On the following day I learned - and was not very pleased about it - that the Flight Lieutenant Meredith who had been so annoying on the boat, was to be my Flight Commander. S/L Winton distributed jobs to the new boys. I got landed with being MT (Motor Transport) officer. Although I could fly a Spitfire I had never driven a car. Didn't bother mentioning that, just determined to do something about it.

As most of the 155 pilots had never flown Spitfires they had first choice of their new aircraft - and, in any case, soon took off for an experience on type and at Armada Road fighter school - leaving us 'sprogs' at Alipore. It was 14 January before I climbed into a Mark VIII Spitfire for a 30-minute 'experience on type' flight. I noted in the log 'Quite an experience. Marvellous machine.'

Then I had to wait until 23 January before my next flight, a 30-minute 'air test' which gave me the opportunity to really try it out. I thoroughly enjoyed the speed, rate of climb and handling characteristics of this aircraft.

At the beginning of February there were three flights in the Squadron Harvard to become familiar with the local area and weather flying conditions and on 12 February formation and aerobatics, followed on subsequent days by search formation, flight formation, dog fights and aerobatics at heights up to 30,000 feet.

On 18 February I note that Flying Officer 'Bish' Bishop and I were 'stooge' aircraft so that B Flight could practise interceptions and attacks. I got to know 'Bish' well, liked him - and at the time of writing (June 2000) - am still in touch with him at Old Portsmouth.

The top pic shows 'Bish' sitting in a Mohawk in the Imphal Valley.

Underneath: Clive 'Smoky' Entwistle, from Southport, and Dave Gardner have a pretend fight on a jeep. 'Smoky' was to be killed during a raid on Yeu in Burma.

3rd and fourth pix below: New Zealander 'Babe' Hunter and 'Smoky'; 'Babe' and me. He was known as 'Babe' because he joined up when he was only about 17 and could only have been 19 or 20 when he was a 155 veteran.

Top right: George Brown, Albert Wittridge and me. George has one of the parakeets, which were plentiful at Alipore, perched on his hand. A month later (see previous page) George was dead. 'Witt' and I still ring each other now and again. He lives in Weymouth, Dorset

Second right: 'Jock' Dalrymple, from Aberdeen, holding the piper symbol which - I imagine - the airman in the cockpit has just painted.

Third: a doleful look from the Wing Engineering Officer, who was trying to sort out why - after we had moved to another aerodrome, Baigachi, north of Calcutta - the Merlin engines, alarmingly, were cutting out now and again. It turned out to be fuel locks caused by poor quality octane petrol.

I wrote a poem about it:-

Oswald Newport, Wing Eng/O

Said: 'To Baigachi I must go'

But Oswald never washed his socks

In sympathy, huge vapour locks

Developed in the system fuel

Cor blimey, ain't that just too cruel!

Towards the end of 1943 the Japs had bombed Calcutta, causing a comparatively small amount of damage but a tremendous amount of panic. As a result, 155 Squadron was to be based mainly at Baigachi but occasionally at other airfields near the city, until the beginning of August. The theory was that we were 'defending the city

and keeping up civilian morale.' But there were no more raids.

Flocks of birds are one of the problems about flying. Manchester Airport has a special squad of bird scarers. We didn't have such luxuries and had far bigger birds to contend with. The pic top left shows us with a kite hawk, just shot down by Jock Dalryrople, holding shotgun on right. I'm third from left. I did inadvertently hit one of these once, over Burma, and it bent my prop tips more than somewhat but I was fortunately able to carry on flying and get back to the airstrip.

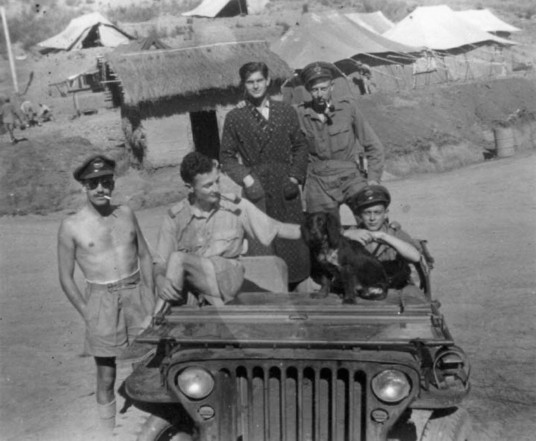

Pic below of group in jeep shows the Squadron 'doc', me (with pipe!), Jimmy Gunstone (who accidently killed himself with his own Sten gun when he tripped over a guy rope just after the war finished) and a Flying Officer Dave Gardner with his dog. Top two pix on right: views of Burma jungles, mountains and a river. T'other jeep pic: on left Brookie, who became my regular number 2, me (with pipe again!), Andy Tough, from Aberdeen, two I can't identify - and Jimmy Nutti, the Ghurka boy rescued from scavenging in Calcutta dustbins by 17 Squadron airmen and more or less adopted by them. Jimmy is also featured on bottom pic, taken by a visiting official photographer who was known, for some reason, as 'Harry the Horse.' He asked me to start up my Spit, DG-K, for this posed picture.

When in the Lake District earlier this year (2000) I found the RAF were using this photograph to identify 155 Squadron in an official book about all RAF fighter squadrons.

Getting back to chronological order, during January 1944 was able to familiarise myself with the Mark VIII Spitfire - and liked everything about it. I found rolls a joy and loops marvellous, although pulling hard on the stick for a loop meant it was easy to black-out. I climbed to 14,000 to test the supercharger, which cut in of its own accord at that height, giving lots more power. I opened the throttle and shot up to 27,000 feet. Coming down, the airspeed indicator touched 450 mph.

The Squadron returned from the gunnery school at Amarda Road and we continued with the 'defence of Calcutta.' That was easy, apart from a few false alarms. The Japs didn't seem to want to return. We learned that down on the docks someone had invented his own air raid warning alarm. Reason: dockers got double pay for working after an alarm had been given!

March 9 became a red-letter day. Didn't realise it at the time but all problems with Flight Lieutenant Meredith were about to be solved.

The CO, Squadron Leader Winton, decided that A and B flight pilots should visit a Ground Control station, one of the few in that part of he world. On the way back, Meredith was driving a jeep with six pilots aboard it, including me. He was travelling too fast on a turn, ran off the track and hit a tree. My head went through the windscreen. (A gash on my forehead was stitched by the doc, who either didn't bother about or didn't have any anaesthetic). Wittridge took off over the nose of the jeep and - as he put it himself - crashed on landing in front of it. Bish dislocated his hip. There were sundry other injuries, including Meredith who cut his knee. He made such a fuss about it that he was taken to hospital. As Motor Transport Officer I then got the job of visiting him there to take a statement about how all this had happened.

Meredith said it was the CO's fault for ordering the run to the radar station! That'll do nicely, I thought. Say no more! I went back and told the CO this. As I thought he would, he blew up and promptly began arrangements to get Meredith off the Squadron. We never saw Meredith again.

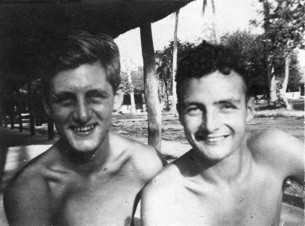

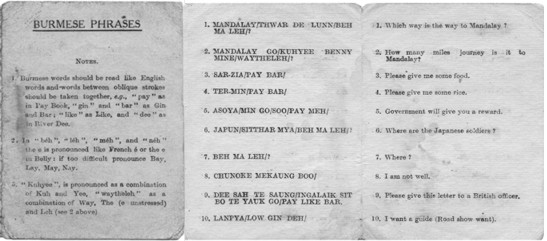

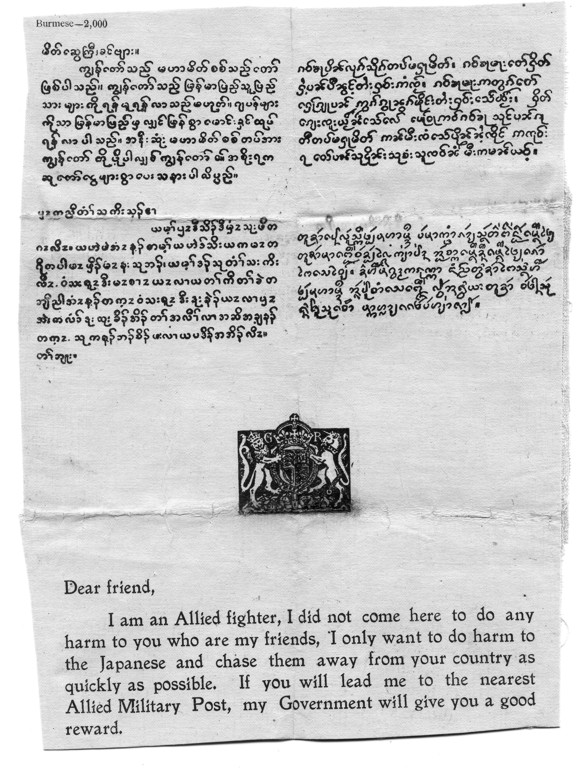

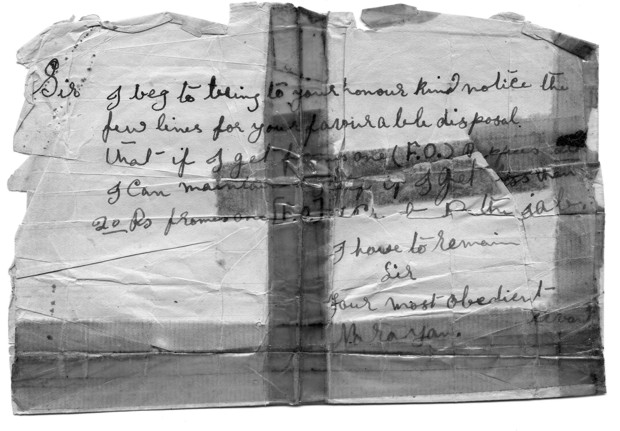

Thought I'd include here one of the 'chits' we were told to carry at all times in case we came down in he hills or jungles and met natives, who might, with luck, be friendly - or might be anything but. Although it promised, in various local languages, a reward for what might be described as 'safe conduct' I'm glad I never had to use it. Highly likely, the natives would not be able to read!

Incidentally, I don't think the Afghan language was included. It should have been because when I was later stationed at Peshawar, near the Khyber Pass on the North West frontier, I was told in some detail what might happen to you if you were unfortunate enough to land in Afghanistan.

Most of March was spent in getting to know our Spitfires better, taking part in Squadron and Wing formations, carrying out dog fighting using camera guns, aerobatics, low flying and experiencing the qualities of the aircraft at great heights, up to around 40,000 feet, as well as practice scrambles and interceptions. Many of these exercises were over Calcutta, to demonstrate to the population that we were there to protect them. We also tried out the two 20mm cannons and four machine guns, firing out to sea.

I learned how hard the Spitfire controls became during high speed dives especially the ailerons. At one time I reached an indicated air speed of 500 mph, which meant that the aircraft was not too far from the speed of sound.

It was during this period, on 16 March, that Canadian George Brown, taking part in a Wing scramble, dived vertically into the ground 20 miles south east of Calcutta and -

as mentioned earlier - was killed.

On 19 March we moved to from Baigachi to a grass airfield known as Acorn, closer to Calcutta. On 8 April Flying Officer Cheverton - who joined the Squadron on the same day as I did - ran out of petrol when returning from formation and section attack but managed to force-land on the airstrip, bending the aircraft somewhat. Three days later, while testing another Spitfire it blew up - for no known reason - and he was killed.

When he arrived on the Squadron Chev had been landed with the job of Education Officer. The C.O. informed me that I was the new Education Officer! At least I did get rid of being Motor Transport Officer.

One of Chev's legacies was the fact that, as a music lover, he had acquired for the Squadron a wind-up gramophone and a set of superb classical recordings. Although - to this day - I know little about music I found I was also supposed to keep up his standards in the music field.

At this point - from January to March and April 1944 - while still honing our Spitfire skills against Japanese raids which failed to come, there was plenty going on elsewhere. Might be helpful to put matters into perspective.

In October 1943 Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived in India. So did I! He had just been appointed Supreme Commander, South East Asia.

The Japs had been sweeping all before them in Burma. They were finalising plans to reach the Indian border. During March they launched all-out attacks on Kohima, near the Burma/India border, and on Imphal in the State of Manipur, which they considered was the Gateway to India.

Mountbatten had orders to turn the tide. He arrived with three Ms in mind - one, to overcome poor morale; two, to fight on during the monsoon period; and three, to combat malaria.

He started by telling the 14th Army: 'You are not the Forgotten Army. Nobody has ever heard of you!' adding, 'But they soon will.'

The policy of fighting on during the monsoon and no retreating meant that the troops would have to be supplied from the air, mainly by a fleet of Dakotas. Fighter aircraft would have to protect these transport aircraft by operating in appalling weather conditions. Malaria was kept under control by issuing Mepacrine tablets. They worked, but turned the skin rather yellow.

His policies worked. The

Battle of Kohima was one of the fiercest of the war in South East Asia, but it was won. Flying during the Monsoon weather was very dangerous but the Army was supplied and the Japs were kept out of the Imphal Valley. The cost was high. 17,587 British and Indian troops were killed, wounded or missing. Five VCs were awarded.

Many of the dead lie at Kohima, where there is a monument with an epitaph reading: 'When you go home, tell them of us and say: For your tomorrow we gave our today.'

Fighting during the monsoon meant mud and misery for the Army; flying in and around towering thunder and lightning clouds, full of strong and turbulent air currents, for the RAF and USAF.

Later, I was to experience near disaster in monsoon clouds as well as having the not very pleasant experience of escorting Mountbatten's Dakota through fearsome thunderstorm clouds from Burma on part of his route back to India.

A major factor in the turn of the tide was the arrival of Spitfires. Hurricanes - and Mohawks - had been no match for the Japanese fighters, which were similar to their Naval Zeros. We called them

Oscars.

On the last day of 1943 the Spitfires destroyed 13 Japanese bombers and fighters. They outperformed the Jap aircraft.

Returning to chronological order, it was in April 1944 that the Squadron quack gave me a fright which I thought meant the possible end of my flying career. In a burst of enthusiasm he hauled the pilots into his tent at the Acorn airstrip, where he had put up an eye chart. After getting me to read it first with the right and men the left eye he told me that the performance of my left eye meant that I could not judge distances. 'Oh, yes I can,' I said. 'Oh, no you can't,' he said.

After a bit of this cross-talk I offered to take him up in the Squadron two-seater Harvard which was parked outside. 'If I don't paint it back on to the ground I'll believe you,' I said. 'So come on, I'll take you up.' 'No you won't,' he said, and made an appointment for me with an eye specialist in Calcutta.

I kept the appointment, gloomily thinking I might be grounded. However, the specialist was quite happy about my distance judgment and eyesight. 'You'll need spectacles when you are about 40,' he said. He was right about that.

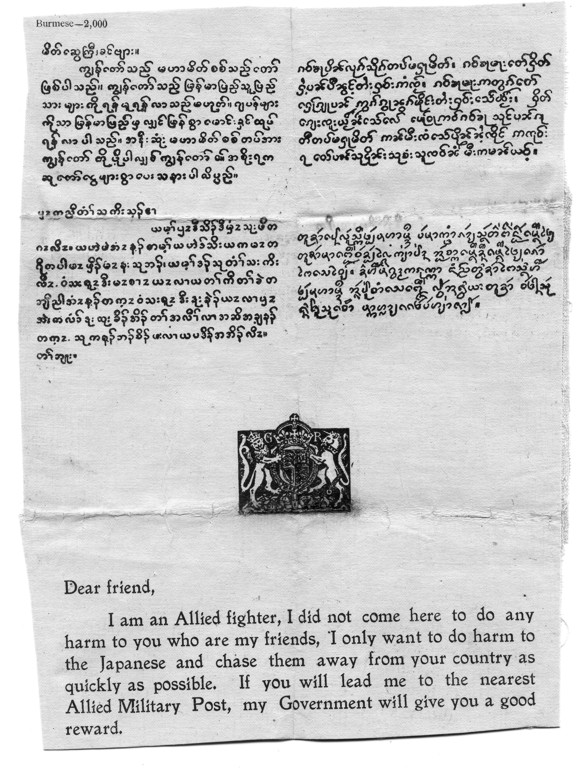

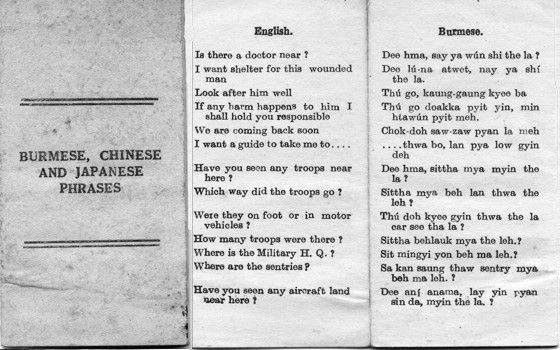

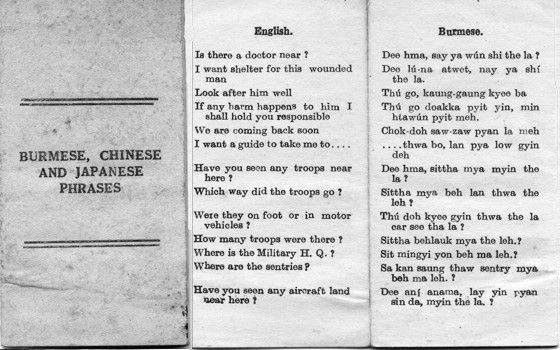

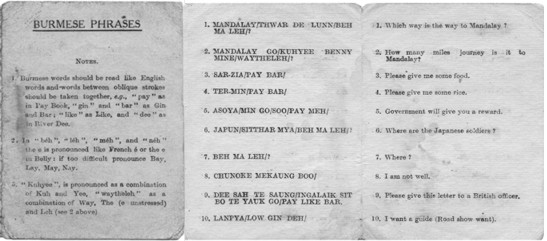

On the opposite page: two more examples of the helpful phrase books with which we were issued. Sample phrases: 'Which way to Mandalay?' 'Where are the Japanese soldiers?' 'Is there a doctor here? But mastering the pronunciation might have been a bit difficult.

At the end of April the Squadron returned to Baigachi and the daily routine of continuous readiness. Squadron formation flights, aerobatics, mock dog-fights, high-speed attacks etc. At one point I flew an extended wing version of the Spitfire - the idea being to make it more manoeuvrable at height - but I didn't like it. Later I also flew a clipped wing Spitfire, which was supposed to increase manoeuvrability when low down, but I didn't care for this one either. I preferred the elliptical Spitfire wings and so did the other pilots.

We had a visit from some Americans, demonstrating their Kittyhawks, to us. Then six of us visited them at their base, Kharagpur, putting on very tight formation for their benefit.

We were still on daily readiness in case the Japs did decide to have another go at Calcutta. On May 1st came my first 'op'. Two of us were scrambled for a 'bogey' - an unidentified aircraft. It turned out to be an American Liberator with its IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe) switched off.

On the same day Canadian Doug Gillon, who arrived in India with me and also joined 155 on the same day, touched his wing on landing and wrecked his Spitfire. As a result he was posted to a maintenance unit at Allahabad, where he tested repaired aircraft! In due course he did return to the Squadron.

We also parted company with the CO, Squadron Leader Denis Winton DFC, who had completed his tour. He invited us to visit him at any time at his home, the address being, he said, Winton Hall, Edinburgh.

The month passed fairly quietly, except that I landed another Job Squadron historian, keeping a day-to-day log of events and writing articles for the RAF Training Manual known as Tee Em. As Education Officer I set up a 'quiet room' and equipped it with maps, magazines, notices etc. In theory, the erks could browse there in idle moments. They didn't bother much.

I heard from Tom, who had completed his tour and collected a DFM (Distinguished Flying Medal) from the King at Buckingham Palace.

On 21 May our new CO arrived, a Squadron Leader Ian R Krohn DFC, known to us a 'Bats'. He was a bit. And, in Calcutta, I met a Flying Officer Jackson, who was also on the same boat to India as I was. He had been involved in the Kohima battle, his Hurricane was shot down, he parachuted out, managed to dodge Jap troops who were chasing him, and walked through the jungle for the next 21 days, surviving without jungle training and little food or water until he was found by our troops. On the strength of this he was sent to a new jungle training camp at Poona - as instructor!

We liaised with a Liberator Squadron, practising attacks while they sharpened up on their evasion procedures and even had a go at night flying, which was a bit tricky in a Spitfire. The flames from the exhaust, invisible in daylight, were dazzling at night.

Then I had an unusual story to put in the Squadron history. We were sitting at readiness when one of the pilots saw his Spitfire taxying past, with a strange face in the cockpit. We galloped towards it, wondering what was going on. The Spitfire was lined up on the runway, the throttle opened and it started to take off. It then went into a ground loop - a very fast turn - and ended balanced on one wing and its tail. Out of it climbed an Anglo-Indian engine fitter.

It transpired that he had applied to re-muster to pilot and had attended a Selection Board where he was told that, owing to a change in rules, he could only be re-mustered to all aircrew categories, as a potential pilot, navigator, bomb-aimer or gunner, to be sorted out later.

He came away with the impression that he had been turned down as a pilot - which he hadn't. As an engine fitter he knew all about how to start Spitfires and had even taxied them. After brooding about matters - and deciding he had been failed because he was Anglo-Indian - he thought he would show everyone that he could be a pilot. However, he did not know that when the Spitfire engine was opened up and the plane increased speed the torque reaction from the propeller made it swing violently to one side, immediate correction being required through use of the rudder.

Had he realised that, he might have got it into the air, but would certainly never have got it down again in one piece. There was a court-martial and he was sent to what was popularly known as 'the glasshouse.'

Violent swings, unless the pilot was careful, were also a feature of Beaufighter twin-engined light bomber aircraft. Some were stationed at Baigachi. During early May one swung so badly that it hit a parked Beaufighter and blew up. The observer managed to jump out but the pilot and an airman, on board for a ride, were killed.

Have a note in my diary that on 26 May I went up for a practice

dog-fight with Witt. Think I've mentioned him before, because we are still in touch, living in Weymouth. Dorset. He was a very good pilot, my note says I could only get him off my tail by using my Spitfire full out, putting the throttle booster through the gate and nearly blacking myself out several

times.

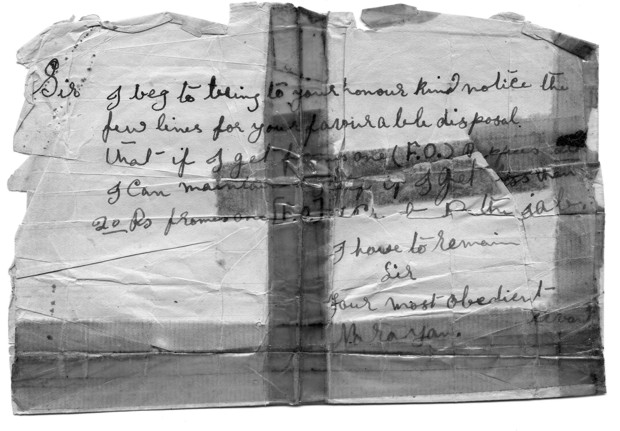

So we moved into June and usual readiness at dawn. News came through that the 2nd Front had been opened in Normandy. Also noted: I sacked my bearer, Nahren. I didn't find this easy, even though he was a lazy blighter, more often missing than not, and he had presented me with a 'more money or I strike' notice, in weird and archaic English, written by the local letter writer, it read:

'Sir I beg to bring to your honour kind notice these few lines for your favourable disposal, that if I get fromes (sic) one (F.O.) Rupees 20 I can maintain myself, if I get less than 20 Rupees fromes one (F.O.) I cannot do the job. I have to remain. Sir, Your most obedient servant, Nahren.' He didn't have to remain. Will include

this now battered and faded letter on the next pic page.

Fortunately, another 155 pilot, with the strangely mixed name of McEdwards - half Scottish, half Welsh? - was moving elsewhere and I was able to bag his bearer, a nice lad called Billy.

June 9 was another notable day. We did a Squadron formation flight over Calcutta, a total of 12 aircraft in the air, the CO leading with two wing men, each with three in line astern. The CO had decided we would do a formation landing to see how quickly we could all get down. This meant landing more or less in pairs, one slightly in front on the right of the runway, the other a few yards behind on the left of the runway.

It wasn't easy because when a Spitfire was near to landing its long nose became raised, completely cutting out forward visibility. My number 1 landed on the right so I came in on the left. The nose reached the raised position blanking the forward view. I touched down, and raced along the runway.

Then, looking out to the side and as much forward as possible, I saw a Spitfire sitting at an angle on the grass with its tail slightly overhanging the runway. My port wing caught his tail. The pilot, a warrant officer, jumped out of his aircraft, slightly damaging his knee.

The Flying Control Officer fired red Very flares and everyone still airborne stayed up until the runway had been cleared.

It transpired that the warrant officer had swung after a tyre burst on landing There was an inquiry into this, of course, but it was decided that the 'prang' was unavoidable.

Trying to carry out educational duties, I booked the padre to talk to the erks. He never turned up. We had a discussion on Communism, the subject chosen by those who attended. Not sure if this was the right sort of topic!

During a height climb with a warrant officer Hick I was puzzled when he suddenly started diving, so I did a wing over and followed him, managing to get alongside. I realised he was only partly conscious, probably suffering from lack of oxygen. I kept shouting to him to wake up - the ground was getting far too close - and fortunately he did recover in time to pull out. I led him back to the aerodrome. The weather at that time of the year was very hot indeed and he had been suffering greatly from prickly heat, which perhaps weakened him a bit. Later, it was decided that he needed to get back to a cold climate and was posted back to the UK.

Around this time I found the Wing Commander treating me as something of an office boy. He had discovered I could write shorthand and type.

I then ran into another educational problem. A group of airmen arrived at my basha and told me they wanted to spend time a bit more usefully by learning something. 'Learning what?' I asked, cautiously. 'French,' they said.

'Oh dear,' I thought, and then asked nervously, 'How much French do you know?' They said that none of them had ever taken any French. I cheered up considerably and agreed to organise classes. Fortunately, I had with me the

Heath's New Practical French Grammar I had acquired at night school in Chorlton. I hope they learned something to their advantage.

It was about this time, towards the end of June 1944, that I learned of the death of my friend Ian Duncan, whose 64 Squadron Spitfire was shot down by flak. He crashed into a French farmhouse and was killed (see earlier reference in 1943).

During July we were intrigued to see a twin-engined twin-fuselage American Lightning fighter come in and land. The pilot came over to where we were sitting on readiness. 'Say, you guys,' he said, 'I've always wanted to fly a Spitfire. You lend me a Spitfire and you can borrow my Lightning.'

It took a while to convince him that in the RAF it was not quite as easy as that to do a quick swop. He flew away again, but the Higher Ups, when they heard about this, thought it was a good idea to have a bit of Anglo-American friendship and co-operation. It was arranged that two of us would fly to their base at Asansol for them to fly Spitfires and that later they would reciprocate by bringing over two Lightnings for us to play with. The two 155 pilots chosen were Flight Lieutenant Tim Meyer - who hailed from Trinidad - and Flight Lieutenant Bert Murray, a South African former Hurricane pilot who was a recent recruit to 155.

For good measure. New Zealander 'Babe' Hunter, another pilot and I flew to Asansol just afterwards and did a bit of tight formation over their 'drome but didn't land - so we didn't know at the time that they both did low aerobatics on arrival and

that Bert Murray performing a low roll, had hit a wing on the ground, crashed and been killed in the middle of the airstrip. Doing exactly the same sort of thing was the manoeuvre that cost Douglas Bader his legs.

Bert's death was, of course, the end of the Anglo-American co-operation plan, so we never sampled flying their Lightnings.

Other matters, around this time....

During dummy attacks on Liberators my airspeed indicator became useless. To land safely, I asked Canadian Warrant Officer Pinch to lead me in. He was a fine pilot but never bothered much about his style of dress nor air force regulations such as saluting officers. Nonetheless, the CO thought his skill and experience deserved a commission and arranged for him to be interviewed by a Commissioning Board in Calcutta. When he arrived some officer in charge of guard duty thought he was so slovenly that poor Pinch was drilled up and down he parade square! He never got a commission but I don't think he was terribly bothered.

There was an airstrip called Red Road - it was just a cordoned off stretch of road in the middle of Calcutta - where I landed one day. To get in, you had to do a steep turn round

Firpo's, one of the best hotel/restaurants in Calcutta, situated on Chowringhee, the main street. It was fun.

We did find time for swimming at the Saturday Club pool, dancing at the 300 Club, and for going to cinemas. The cinemas were absolute bliss, no matter what the film, because they were air conditioned. It was pleasantly cool inside, no matter how hot and humid it was outside.

Flying at the time included practise firing of machine guns and cannon out to sea. I note that I also took up my airman fitter. Leading Aircraftsman Churcher in the Squadron Tiger Moth. During aerobatics the engine started running roughly. No wonder. A spark plug had fallen out!

The monsoon period got under way, with torrential rain coming down, often very suddenly. I took off in sunshine one day and got back to find the runway flooded. It meant landing with the flaps up - therefore much faster than usual to prevent the flaps being damaged by the water. It was a long landing run.

Another interesting experience came when flying with Jock Dalrymple round clouds towards a belt of rain when we found ourselves in the centre of a completely circular rainbow.

Towards the end of July - 1944 - we were briefed that we would soon be moving to the Imphal Valley to relieve 615 Squadron and were told that operations against the Japanese could involve long distance flying. We practised using long-range tanks, huge things which spoiled the airflow and reduced airspeed

Pictured right (top) pilots of 155. That's me, with pipe, helping CU squadron Leader 'Bats' Krohn to prop up the 'basha'. I'm wearing the latest issue jungle wear, the

Beedon suit. Will say a few words about this monstrosity later.

On 10 August 1944 the whole Squadron was on early full readiness to move to Palel airstrip in the Imphal Valley, on the border of Burma. Heavy rain was pouring down, visibility was terrible, monsoon clouds were very low and we wondered whether the exchange with 615 Squadron would be postponed.

Much to our surprise, a lone Spitfire emerged from the murk and landed. Out of it climbed an ashen-faced 615 officer. 'Are you an advance pilot?' we asked. 'No,' he replied, rather shakily. 'The whole Squadron set off, we got broken up into some terrible monsoon stuff and I don't know what has happened to all the others.'

In due course we learned that 16 Spitfires, led by 615's CO,

Squadron Leader Dave McCormack, DFC and Bar, had taken off from Palel for Baigachi in what seemed reasonable weather and flown in formation until just after passing the point of no return - the point at which there would be insufficient fuel to return to Palel - they met huge black and turbulent storm clouds which extended from around ground level thousands of feet upwards. An attempt to climb above and find a way through failed.

In the blackness of the cloud the Spitfires were tossed about like toys. Pilots lost control. Eight of the 16 aircraft were lost. Four pilots were killed, including the CO. Three survived but with leg injuries after baling out. One escaped after crash landing in a paddy field.

The remaining eight pilots managed to regain control of their Spitfires and reach Baigachi.

It was the biggest single loss of Squadron aircraft and pilots in the shortest space of time in Burma.

(See account of the monsoon disaster written by a 615

pilot who was involved in it).

155 CO, Squadron Leader Krohn, decided to send A Flight to Palel, keeping B Flight behind until 615 were re-organised. I was in B Flight. We took off for Palel four days later, on 14 August.

Palel was a small airstrip in the South East comer of the Imphal Valley. It was half-surrounded by what were described as 'hills.' Hills! They went up to 8,000 feet. We discovered we had to cross them to fly into Burma.

On the following day I see that I did a 90-minute sector reconnaissance flight, taking a look at the Imphal Valley and surrounding areas, followed on the next day by a look at Burma itself. Later in the day it was a 105-minute operation, escorting an Anson which was dropping propaganda leaflets after Hurricanes had dive-bombed a Jap HQ at Tonzang.

Then came a 'rhubarb' - looking for targets - along the Chindwin. We reached a Japanese encampment at Homalin and tried out our cannon and machine guns on military-style buildings. Other possible targets included barge traffic on the river. Found a barge on 28 August, while escorting Hurricane bombers, and sank it.

On 3 September six of us, led by Flying Officer 'Jock' Dalrymple ('Jock frae Aberdeen' as he usually signed things), had a lesson in monsoon flying.

We set off in poor weather to escort Dakotas to Minthami, where they dropped supplies into a jungle clearing for ground troops. They set course for home and, on nearing the Imphal Valley, turned towards their own base. We headed for Palel, but suddenly found ourselves in a black cloud full of strong turbulence which threw us about. I just saw Jock's aircraft, in front of me, apparently going into a stall and got a glimpse of Flight Sergeant 'Mac' McCormick, on my left, going down in a spiral dive when I had to haul back on the stick to miss another Spitfire. After that, I was too busy trying to sort myself out than to worry about what was happening to others.

My blind flying instruments - artificial horizon, giro compass and turn and bank indicator - were going haywire, and my airspeed was falling. I thought I must be climbing and put the stick forward to get my nose down and opened the throttle. I began to lose speed even more rapidly. Think I must have been climbing upside down. Then I began to lose altitude and that worried me enormously. I was at about 9,000 feet and knew I must be somewhere near those 8,000-foot high 'hills'.

Fortunately, 1 came to a slight break in the clouds, got brief look at the ground - which wasn't very far away - and managed to orientate myself enough to straighten out, start climbing and fly level long enough for the instruments to settle down again. I set course for where I thought the Valley was and broke out of the cloud again to discover I was heading for Palel.

Four of us landed. Jock and Mac were missing.

Both turned up again, although looking a bit worse for wear. They had baled out, landed in the mountainous jungle and managed to walk back, Mac in three days and Jock in four.

The next 10 days were taken up with escorts to more supply-dropping Dakotas, to VIPs flying in little L5 aircraft to and from jungle airstrips and on 'rhubarbs'. Then I was given the job of carrying out a Court of Inquiry into the accident in July at the American Asansol base which caused the death of Flight Lieutenant Bert Murray.

On 16 September I took the Squadron Harvard and, with Pilot Officer Paul Ostrander as passenger, flew via Argatala (for re-fuelling) and on to Alipore, Calcutta. Leaving Ostrander in Calcutta I flew the next day to Asansol where I interviewed Americans who had witnessed Bert Murray's crash. When en route back to Calcutta I realised there was an electrical storm behind me but thought there was time to land at Bishenpur to refuel. I popped into the mess there and came out to take off again to discover, the ground erks had tied down the Harvard because the storm - big black and blue clouds containing lightning flashes - was just about sitting on the end of the runway. I didn't fancy spending the night at Bishenpur so I got them to untie it and took off, heading away from the storm.

My return flight to Alipore was quite speedy because I had the strong winds of the storm behind me. I landed at Alipore, told them this storm would soon hit them, and went into Calcutta to find Ostrander, who had been buying supplies of hooch etc for us to take back to the Squadron.

Two days later, this time with Ostrander piloting, we flew to a Repair and Salvage Unit at Salbani where I interviewed crash repair experts and then flew back to Alipore.

On the following day, 20 September, we flew to Baigachi where I wanted to talk to Flight Lieutenant Tim Meyer, who led the two-plane trip for the proposed RAF/USAAC 'exchange' flying programme. By this time, Meyer (who hailed from Trinidad and Tobago) had been posted from 155 Squadron and promoted to Acting Squadron Leader to take over the devastated 615 Squadron - now re-equipped with American Thunderbolt fighters. He said that he and Murray had agreed to do low aerobatics before landing at Asansol, and was obviously worried that my report might result in his losing his new command of 615 Squadron.

I mulled all the statements over as we flew back to Palel, with Ostrander piloting and me relaxing in the back seat.

I didn't relax for long. As we neared the Imphal Valley 'Ossie' climbed to around 10,000 feet to make sure we were over the top of the 8,000-foot Imphal 'hills' - and the engine started cutting out. We started heading downwards. What was wrong? It dawned on me that it could be that the carburettor was icing up at this altitude, starving the engine of fuel. The carburettor de-icing control was in the front cockpit. All I could do was keeping shouting to 'Ossie': 'PUT THE CARBURETTOR HEAT CONTROL ON.....NOW....FAST!!!' (or words to that effect). The message got through, he did - and the engine started running smoothly again.

I then started, my report. As the Number 1, the leader of the two aircraft, Meyer was responsible for his Number 2 and ought not to have led him into low aerobatics. The duty of the Number 2 was to follow his leader. However, to put the blame entirely on Meyer would probably result in his demotion, leaving 615 Squadron again without a Commanding Officer. I decided to state that although then Flight Lieutenant Meyer was wrong in leading into low aerobatics, his number 2 was of equal rank, also being a Flight Lieutenant, and therefore could have refused - and in fact should have refused - as his flying time was mainly on Hurricanes. He had little flying time and experience on Spitfires.

Good and experienced pilots were needed. Meyer was a good pilot and very experienced. The higher-ups accepted my report, Meyer was reprimanded and it was left at that.

Back to operational flying. On 24 September I was detailed to go on what was described as an 'offensive recce' over Japanese-held territory at Kam and Mawlaik but this was called off after ten minutes' flying because of bad weather.

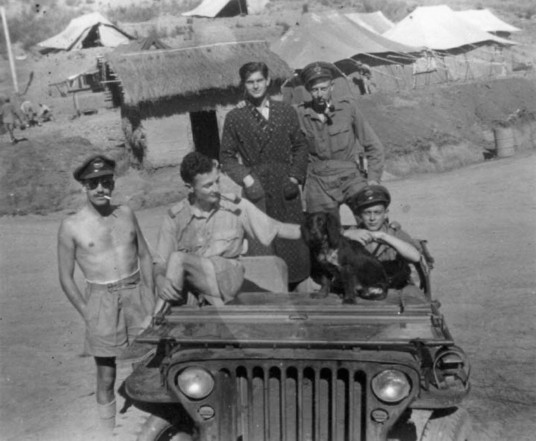

Thought it might be an idea at this point to give some idea of the luxurious accommodation we enjoyed in the Imphal Valley. Just behind the chaps in the Jeep is a typical 'basha', which was the height of comfort usually occupied by officers. Behind are the tents which provided shelter for ground crews. As usual, you'll spot me easily, puffing at a pipe. The others in the Jeep (L to R clockwise) are Jimmy Gunstone, who flew in Malta before his posting to Burma; 'Smoky' Entwistle, from Southport (who was also a pipe smoker, hence the 'Smoky'); and Dave Gardner. Standing on the left is the Squadron Medical Officer.

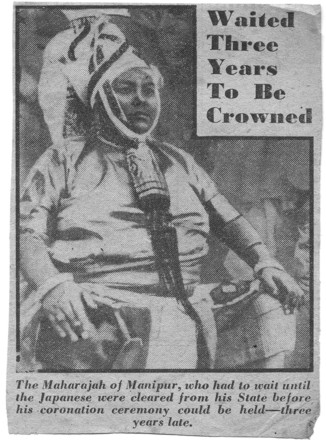

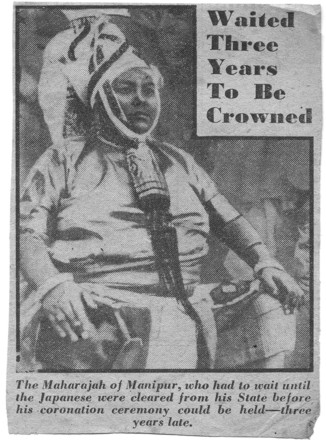

The handsome fellow below is the Maharajah of Manipur. He was thought to be the most poverty-stricken Maharajah in India. He looks quite well-fed, though.

Mentioned Beedon suits on page 79. This was someone's bright invention, supposed to make life easier for us. It had more pockets than a conjuror to stash away maps etc, but it had a big snag. A pocket in the leg had been designed to hold a folding kukri, for hacking your way back through the jungle but as you ran out to your aircraft it thumped your knee and just about broke your kneecap.

We all carried kukris, the normal design, strapped to our belts. Far better.

Sept 25 1944 was a lively day. A Jap reconnaissance aircraft known to us as a

Dinah came near the Imphal Valley and was shot down by a 152 Squadron Spitfire. The Japs obviously wanted some information desperately and we thought they would come again. They did. Four 155 Spitfires were scrambled. Listening on a ground radio we heard Pilot Officer Wittridge shout, 'It's another Dinah. He's heading for cloud.' Fairly soon afterwards a lone Spitfire shot across the airfield. It was Witt's Number 2, Flight Sergeant Lunnon-Wood - known as Timber - all his guns having been fired. He landed and climbed out, shouting: 'We got it. It blew up....poof...just like that.' Witt also landed, beaming.

We hoped for more scrambles. There was one, almost immediately. I and others hurtled into the air but there was nothing doing. The plot turned friendly, presumably one of ours who had possibly not switched on his IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe).

On 27 September I air-tested a new Spitfire which had just been delivered. It was great - very responsive. I noted that I could do a half roll and dive at 4000 feet and easily pull it out in 2000 feet.

I received a letter from Tom, from which is seemed that he might be about to undertake another bombing tour, the chump. I later learned that he and another air gunner had, in fact, after completing their first 30 op tour, had volunteered to do more ops to help an inexperienced new pilot and crew - which was short of two gunners. The pilot, known as 'Bluey' Mottershead, later told me that their guidance had been invaluable in helping him and his crew to survive. Both Tom and the other gunner, Ted Smith, certainly deserved their awards of the Distinguished Flying Medal.

Tom was promoted to Pilot Officer and posted to Lossiemouth as Gunnery Officer, training new recruits. He developed new training methods and, while at Lossiemouth, reached the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

Meanwhile, back in Burma, it was becoming clear that the Japs were in difficulties but were determined to make last-ditch efforts to regain the initiative. During September and October we flew many escort duties from Palel in the Imphal Valley when DC3 (Dakotas) were on supply-drops to advancing ground troops. These took us to places - no doubt never heard of then and for that matter now - in Britain. I note that there was Gazanyo, Kalewa, Yasacyo, Tiddim, Natchaung, Myittha, Fort White and Kindat.

To assist the 14th Army, we also carried out 'rhubarbs' - searches for enemy targets - to straffe. When with Jimmy Gunstone as my number two we spotted what looked like a Japanese tea party going on at Yeu, a railhead, and soon spoiled it. On another trip we discovered Jap headquarters at Kalewa. They shot at us with small arms; we replied with our 20mm cannons. We pranged river rafts and tried to bring down telegraph poles.

On October 16 - my 22nd birthday - the Squadron went on a long distance trip to straffe Jap fighter aerodromes at Shwebo and Onbauk. Witt and I provided high cover while the other eight went in low to shoot at anything in sight. They damaged an aircraft or two and buildings but most of the Jap planes must have been withdrawn to other dromes farther away.

Around this time my aircraft, K, started misbehaving with boost surges. Despite all ground staff efforts, a couple of air tests continued to show that something was badly wrong and that K went off to a maintenance unit. Another K was produced and it was fine.

Although quite a lot was happening in me air, me airmen found time hanging on their hands a bit, so I note that on 24 October I ran another class in French. I blessed Mr Heath and his

New Practical French Grammar, but I don't think he would have thought much of my pronunciation.

Our Burma intelligence system seemed to be working much better. On 26 October (brother Walt's 20th birthday - he was on flying training in South Africa) the CO, Squadron Leader 'Bats' Krohn, told us the Jap air force high-ups were planning a surprise raid on Imphal Valley airstrips. He devised a plan. In addition to having us on top readiness to tackle the Japs immediately, six aircraft, fitted with 90-gallon drop tanks, were to climb high and wait, then drop the tanks (they impaired flying ability) and have a go anywhere over the Valley as well as catching any homeward bound Jap Oscar fighters. He said that American-built Thunderbolt fighters, with longer range than Spitfires, would also chase the Oscars.

We were on super readiness for the next five days. Then, at the end of October I was told that I had been detailed to go on an air fighting instructors' course at Amarda Road Air Fighting Training Unit. run by Wing Commander Carey. He had fought from the early days of the Burma war, on Hurricanes, as a sergeant pilot and risen to Wingco. So, on 3 November I drove to Imphal where I boarded an American DC3 to fly to Dum Dum, just outside Calcutta. I managed to get into Aircrew House in Calcutta and amused myself until catching a train to Amarda Road on 7 November.

In the meantime, 155 Squadron Canadian pilot Paul Ostrander turned up in Calcutta. He told me that on 5 November, two days after I had left, the Japs arrived over Palel as dawn was breaking and started straffing away. The sneaky Japs had flown low through the night to catch us on the hop. They nearly did. Most of the Squadron managed to get airborne and there was a ding-dong battle right overhead. Witt had got an Oscar, so did a chap called Parke. A newish pilot named Gentry was missing. He was never found.

Why, I thought, did the Japs have to wait until I had left? On second thoughts, maybe it was just as well!

Another thing had happened on my departure - a new CO,

Squadron Leader 'Ginger' Lacey had turned up to take charge temporarily while our CO, 'Bats' Krohn, was away. Lacey was an ace - in fact the ace - Battle of Britain pilot. He arrived on the day of the Jap raid. In the book 'Ginger Lacey - Fighter pilot' he says 'How the Hell did the Japs know I had been posted here?'

Lacey, started the war as a sergeant pilot, flying Hurricanes in France. Later, still on Hurries, he became top scorer in the Battle of Britain. He destroyed 18 enemy aircraft, including the Heinkel which bombed Buckingham Palace. By the end of the war his total was 24 (one a Jap Oscar) plus four probables and six damaged. He held a DFM and Bar and a Croix de Guerre.

The top photograph, sent to me by Witt, shows Lacey congratulating Witt on shooting down the Oscar.

By the time I returned to the Squadron in December, Lacey had departed to command neighbouring 17 (Spitfire) Squadron.

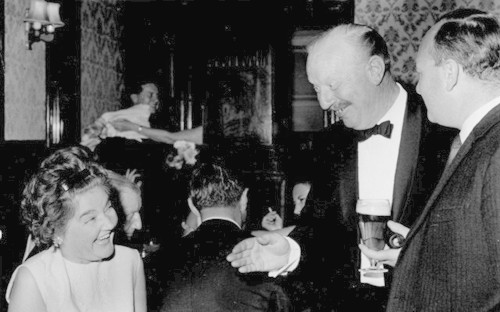

I was not to meet him until the late 1960s when Beth and I were in Blackpool. By that time I was doing some PR work for Shell Mex and BP, as it was then known. The Company had illuminated a tram with its logos and I went, with photographer John Cooper, to publicise this. Beth joined in.

The Illuminations that year were switched on jointly by Douglas Bader and 'Ginger' Lacey. During a reception party, I had a word with Lacey, we reminisced a bit about Burma and John took photographs (see lower pic). 'Ginger', who had at last put on a bit of weight, is clearly shooting some kind of a line to Beth. That's me on the right.

After the war 'Ginger' taught at a Yorkshire flying training school and ran an air freight business. He died on 30 May 1989 at the age of 72.

We didn't see Bader. Perhaps he had turned in because his tin legs were liable to hurt after he had been standing or walking about. But I did meet him in later years when he attended a meeting of the Churchill Club at the Midland Hotel as guest speaker. (I was the Club's honorary publicity chap.) Bader drove himself from somewhere in the South, arrived at the hotel, left his car at the main door and stumped up the steps. 'You can't leave your car there,' said the doorman. 'Yes, I can,' said Bader, and went in, going straight up to his room to take off his legs to have a rest before the evening.

We had a chat before the dinner. Standing next to him I found we were about the same height. He lost some height when his legs were first made. 'Well,' he said, 'You are just the right height and build for a Spitfire pilot.'

His speech was not very long and mainly consisted of war-time RAF-type stories. Think his legs were still bothering him. Some of the those attending were miffed, believing he should have talked for much longer. Personally, I and most of those present thought he had done us proud by attending. It was an honour to meet this courageous man who had done so much to inspire other pilots during the war and who, by example and encouragement, had helped many people to face up to similar disabilities.

At the top, another photograph taken at the Blackpool reception. Ginger and I did a fair amount of reminiscing.

Going back to chronology, after a few days in Calcutta I caught a train to Amarda Road Air Fighting Training Unit, arriving there on 7 November 1944 and joining Course Number 20.

First item on the programme: a Course photograph. That's me, second from left, front row.

We were a mixed bag, ranks ranging from Warrant Officer to a couple of Squadron Leaders, plus two Fleet Air Arm pilots from the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable, and an Army chap. Sub-Lieutenant McKinnon, is extreme left, front row; the other Navy flier. Lieutenant Commander Bigg-Wither, is fifth from left. On the left, back row, is an Indian pilot. Flying Officer Rollo, a handsome chap - so much so that his face was featured on adverts throughout India promoting Tenor cigarettes. The Army pilot. Lieutenant Carter, is third from right, back row. Don't really know why he was on the course.

The training was to last for four weeks - and it was certainly intensive. In addition to piling up 43 flying hours on dog fighting and cine-gun firing exercises against other fighters and Liberator bombers; air-to-air live shooting at very small drogues and air-to-sea shooting, we spent many more hours in classrooms swotting up subjects such as trajectories, muzzle velocity, angles of attack, deflection, bullet groups and patterns, rates and density of fire and ballistics. I still have an exercise book I used at the time, full of diagrams and mathematical formulae, etc, etc.

Our ability to deliver lectures was checked out in various ways. For instance, you would be, without warning, hauled out in front, given a subject and told to talk on it for 10 minutes. I haven't forgotten my subject: it was 'Door knobs'. I certainly have forgotten whatever I found to say about them.

I realised how little I had been taught, up to that time, on the ins and outs of air fighting.

My first flight there was on 9 November, carrying out range estimation, flying - for the first time - a Mark V Spitfire. It made me appreciate the immensely superior performance of the Squadron's Mark VIII Spitfires. (The Grangemouth Spitfires were Marks

I and III).

The air-to-sea firing was a real test of flying skill as well as marksmanship. You had to fly at low level towards a cliff edge overlooking the sea. Instructors were based at the top of the cliff. You were supposed to fly so low that they would not see you coming until the last moment. Out to sea - but not very far out - were some black pillars of wood, just jutting out over the water. You had to haul the aircraft up before reaching the cliff edge, half roll over and straighten out into a steep dive to get your sights on to these targets to put in as long a burst of fire as you could, then pulling out before you went into the sea. It wasn't easy!

Another exercise was flying a two-seater dual control Harvard from the back seat, with an instructor monitoring matters from the front seat. You carried out cine-gun firing at other aircraft while peering through a long tubular sight. To put it mildly, the view was a bit restricted.