1940-1942

Harking back a bit, 1940 was, of course, quite a traumatic year, taking in the retreat from Dunkirk, the narrowly-won Battle of Britain and the start of the bombing of Britain.

Vivid in my memory are the speeches of new Prime Minister Winston Churchill. What he said and how said it put new heart into the country and certainly into me.

A corrugated Anderson air raid shelter was installed in our back garden. Dad turning the remainder over to potatoes, cabbages and other vegetables. He started at Metropolitan Vickers in Trafford Park, helping to build Lancaster bombers.

The Anderson shelter was cold, dank and miserable. When the air raid siren sounded Tom, Walt and I were not keen on getting out warm beds and into it.

On December 22 and 23 1940, the Luftwaffe launched its biggest raids against Manchester. In Chorlton, houses were wrecked and people killed and injured. The Rivoli Cinema, our newest, was wrecked beyond repair. A gas main was damaged and set on fire, a mass of flame leaping up, in Barlow Moor Road. A somewhat inebriated air gunner offered to sit on it to put it out. He was restrained. Incendiaries peppered the streets, including Thorneycroft Avenue. We chucked sand over them.

All this was little, of course, compared with the damage in the city. I cycled into Manchester, having to carry the bike much of the way because of bricks and rubble in the road - especially in the Shambles area which really was a shambles, only the olde-worlde

Wellington Inn still standing. I joined a Press Exchange group outside the battered Corn Exchange building. 'I've made it,' I said to

Press Exchange Secretary Bill Holliday. 'Well, you might as well push off again,' he said. 'Your job's gone!'

Reg Pullin, Bert Stone and I went into the building, climbing over rubble, reached the office, and rescued typewriters and other essentials. We moved to the Manchester Press Club and set up in business again, staying there until the Corn Exchange was cleaned up and pronounced safe. Half a century later the IRA damaged the building even more!

By December 1940 I had started, at the age of 18, to take on journalistic work which I would not have reached for another year at least. However, older Press Exchange members were disappearing into the Services.

My diary for January 1941 contains details about police court and other reports which I was doing - and payments such as 10 shillings from the Press Exchange for a week's office boy work, £1 from the Middleton Guardian, etc. Total income for the month of January 1941 was no less than 13 pounds five shillings (£13.5.0, as we wrote it then). February was not quite so good, being six pounds 15 shillings (£6.15.0).

Weekly newspapers paid three halfpence (1½d) a line!

One of my Middleton Guardian reports included the fact that a local cinema had been damaged. We were not allowed to print that it was the Victory cinema in Moston. That would have given the Germans information about the location of their bombing - and 'Lord Haw Haw,' broadcasting for the Germans could have made fun of the fact that it was called 'Victory'. He was a chap whose real name was William Joyce. He was shot for treason after the war.

I was also writing stories for exciting publications such as the Timber Trades Journal, Confectionery Week and the Fish Trades Gazette, and doing reports on Park Tennis and Water Polo matches. It was all worthwhile experience.

Intending to volunteer for the RAF I also started studying Morse Code, Signalling, Geometry, Trigonometry and wireless - not to mention buying and swotting up a book called 'Teach yourself to Fly!'

On May 29 1941, while pedalling round delivering 'copy' to newspapers, I diverted to the RAF Recruiting Centre in Dover Street, near the University, and volunteered for aircrew, filling in masses of forms. Three days later there was another German raid. Among the damage, the Assize Courts were wrecked.

On July 10 1941 I went to an Aircrew Selection Board at Cardington RAF Station, having to pass a medical and an interview to become a u/t (under-training) pilot. Pleased to say I did. Then had to await call-up, which arrived in September. I went to the Aircrew Receiving Centre at Lord's Cricket ground on 12 October, was inoculated, vaccinated, put through umpteen psychological, physical, educational and other tests, was assessed as possible bomber pilot (!), and arrived at

Finningley RAF Station, Yorkshire, on 27 October 1941 for Initial Training.

I remained at Finningley until early February 1942, being put through an intensive course of ground studies which included maths, signalling, hygiene, aircraft recognition, throwing live grenades, gas exercises (including taking the gas mask off in a room full of some kind of gas) and bags of discipline, marching about, guard duties and what were described as 'barrack room sports' - cleaning the barracks from top to bottom and then taking a freezing cold shower.

There was bags of snow that winter, so much so that we raw recruits were handed shovels and told to clean the snow off the runways. That kept us warm.

There was also supposed to be a 'flu epidemic so we had to sleep with the windows open, waking up to find the bed snow-covered.

It was at Finningley that I met Corporal Basil Hill, who did most of the work on the educational team. He organised a debate on the subject 'The pen is mightier than the sword' and got me to propose it. We won the debate by 239 votes to 16.

Think he must have been responsible for recommending me as a possible officer. I had to go before the Group Captain. He seemed pleased that I had been in journalism and presumably agreed to endorse the recommendation.

(Met Basil again, with Beth, in 1950 when on honeymoon at Babbacombe. He had spent some time as an Education Officer in Aden and, after demob, became a lecturer at Exeter University).

Finningley was an Operational Training Unit, with trainee crews flying Wellingtons and Manchesters. Manchesters were the twin-engined, underpowered, predecessor of the successful four-engined Lancasters. I got my first flip on 24 December, joining a crew as a passenger on a practice bombing raid from 8,000 feet. Thoroughly enjoyed it - but still hoped to get on fighters.

Was at Finningley until 5 February, then - promoted to Leading Aircraftsman - sent to Brighton, being billeted at the Metropole Hotel, enjoying cross-country runs and drills in freezing weather until 4 March, when I arrived at

Theale, near Reading, to try my pilot skills on a Tiger Moth.

The photographs must have been taken about this period. Walt had become a butcher boy at the local Co-op and joined the Home Guard. I was trying out my flying kit while on leave. Tom was home at the same time, so we posed with mother at the back door of 15 Thorneycroft Avenue.

At Theale - 26 Elementary Flying School - we stayed in a mansion house which had grassy grounds large enough for a Tiger Moth. The idea there was to assess whether you might have enough ability to become a pilot. No use sending you overseas for flying training if you were hopeless from the start!

We were all bursting to get into a cockpit to show that we could demonstrate flying ability, enough to go on a first solo. However, snow held up matters for a couple of days, so it was 6 March before I climbed into the front seat of a Tiger, with instructor Flight Lieutenant Holder as back-seat driver, for familiarity with cockpit layout and air experience. On subsequent days, with different instructors, I sampled straight and level flying, climbing, gliding and stalling, medium turns, taking off into wind, gliding approach and landing, spinning, and powered approach and landing. Finally, on 23 March 1942, after 12 hours' instruction, I was allowed to fly solo for the first time. I took off, I sang, I patted the Tiger, I did a circuit and landed ten minutes later. I was happy.

On 1 April I went to Manchester's Heaton Park to await an overseas posting, being allowed to stay at home instead of being billeted in draughty and freezing Nissen hut. Also there was

Ian Duncan, with whom I was to become particularly friendly.

On 7 April we left Heaton Park in the middle of the night, boarded a train and arrived at Gourock. As dawn was breaking we boarded a Polish ship, the

Batory, for the Atlantic crossing to Canada. Also on board, film actress Anna Neagle.

There was an alarm in mid-Atlantic, escorting destroyers dropped depth charges and we were told a U-boat had been sunk.

We reached Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 17 April and were taken by train to Moncton, New Brunswick, to await posting to Elementary Flying Training Schools.

We all posed for photographs with our white aircrew cap flashes and Leading Aircraftsman rank badges. The

top photograph shows me with three friends I met at Finningley.

The Canadian welcome at Moncton was marvellous. Many invitations to home hospitality were received. A Doctor and Mrs Fitzpatrick gave me a meal at their home and took me out in their car.

The second row, left hand pic is their home,

the middle one is me relaxing in it, the other various parts of Moncton and a tableau at nearby St Anselm. The

bottom photograph is of Magnetic Hill, where water in the ditch appears to be flowing upwards.

During nearly a month in Moncton we got to know each other better and the local people.

Left top pic shows Charles helping a timber expert to load his lorry and strolling, camera in hand. The next three are of me posing on a rail by the River Petitcodiac and beside a WW1 artillery piece, watched by some little lad, and Charles sitting on some ancient cannon.

We played table tennis at the YMCA, danced at the Masonic Hall, and sampled the local cinemas.

Impressions of Canada? Well, we were all first struck by the fact that was no black-out, that chocolates, sweets and similar things were not rationed. We tried and enjoyed CocaCola, listened to adverts on the radio - unheard of then in Britain. The cinemas, mainly of timber construction, had hard wooden seats. For this reason, smoking was not allowed - not because of today's anti-smoking campaigns.

Dancing? Not waltzes and fox trots, but dervish whirling. We have caught up with that here, of course.

Factories were surrounded by serried ranks of cars. In the UK there were cycle parks, not car parks. A long time later we caught up with this, too, of course.

I bought a dinky little camera which I had for umpteen years, eventually presenting it to daughter Ann.

But life was not all ease. We were put on guard duties and fatigues - the latter meaning working in the huge kitchens, washing up hundreds of plates, knives, forks and spoons in big, steaming dishwashers. Some of us were good at vanishing when these chores were being allocated. In fact I wrote a story about the 'Moncton ghosts' - erks who could never be found when 'volunteers' were being sought for such jobs.

In the main, the weather was pleasant but an icy wind could turn up unexpectedly to freeze you, particularly at night. I see a note in my diary that while getting very cold on a night guard duty,

Ian Duncan - with whom I was to become very friendly - sent me a bag of sandwiches! A very kindly thought.

Practically everyone we met in Moncton was friendly and hospitable and very anxious to know what life was like in the UK, especially existing through air raids. In their homes they nearly all had framed pictures of the Royal family.

Then, on May 20 1942, it was 'all aboard' for a long train journey to Neepawa, Manitoba, for elementary flying training on Tiger Moths. The train seemed huge by UK standards.

Ahead was a three-day, 1,600-mile journey on three different trains from New Brunswick to Manitoba,

at first running for hours alongside the St Lawrence River.

My new camera was in action, taking a shot as the train curved by the riverside into a tunnel;

at a pause for some reason when we got out to stretch our legs; to picture Quebec on the other side of the water;

to show the excellent meals which were served, and the sleeping arrangements, the seats being extended to make bunks.

We were fascinated by the scenery, totally unlike the UK - lots of huge lakes, mile upon mile of forest, occasional logging camps. Now and again there were what looked like little dolls house timber buildings by the side of the water and often seaplanes moored nearby.

We ate, we slept, we changed trains at Montreal to Canadian Pacific and, on the morning of May 23,

woke up to arrive an hour or two later at Winnipeg,

to a great reception by local ladies who were waiting on the platform to distribute sweets, cigarettes and magazines - and ask questions

about the war and Britain under the blitz.

Another train change, then on to Neepawa.

through flat prairie plains.

We had arrived at Number 35 Elementary Flying Training School, set up under what was then described as the Empire (later the Commonwealth)

Air Training Scheme.

We were allocated to wooden billets with two-tier bunk beds - and then rushed out to explore the aerodrome with its de Havilland Tiger

Moths, similar to those we had flown in Britain.

One obvious difference, the Canadian Moths had enclosed cockpits.

Clearly, they would provide more cockpit comfort and less internal wind noise.

We were impatient to start flying, but first we all had to have three inoculations.

I had developed a headache and sore throat from somewhere and wasn't feeling at my best, so I took to my bed for a day.

I took to the air again with instructor Sergeant Shoebridge on 26 May for a 30-minute air experience flight,

familiarity with cockpit lay-out, the effect of controls and straight and level flight.

I loved it.

I was also pleased to discover that, in fact, a Warrant Officer Winder was to be - in the main - my instructor.

My best instructor at Theale had been a Pilot Officer Winder, so I thought this was a good omen.

One of the first things to be done: pose for a course photograph.

That's me, fourth from left on front row. Ian Duncan is extreme right, front row.

When at Heaton Park I had been down on a draft due to go to the USA for training leading to a course on Catalina flying boats at Pensacola.

Almost at the last moment someone, probably a WAAF admin type, discovered there were too many names on the USA draft so they adopted the

simple solution: delete the first six - alphabetically listed - names and put them on the lists for the Empire Air Training Scheme in Canada.

I remember four of the names - Beresford, Butterfield (that's him, sixth from left), Duncan and Edwards.

Such are the things which govern your future in the Services!

My friends Charles and Jeff Newman (not related) went to the USA.

I met them from time to time later in Detroit.

However, both failed the American training, which was vastly different from that in Canada.

In fact, the RAF powers-that-be got worried by the number of trainees failing in America.

It didn't say much for RAF selection and preliminary training.

As a result, a panel was established in Canada to assess whether these cadets should be given a further chance in Canada.

Many were, and went on to become excellent pilots.

We had been told that the weather in the prairies could change violently and suddenly.

It certainly could. On the day after my first flight I woke up to discover that an overnight storm had turned the aerodrome into a quagmire.

In fact the parade ground looked more like a lake, the flagpole sticking out of the water like the mast of a sunken ship.

We had also been told about the high winds which could develop very speedily, blowing with such strength that a Tiger Moth, flying into the wind, would hover over the ground like a helicopter and in some cases fly backwards! I was to sample these aerial conditions in due course.

There was no flying that day but, early morning strong winds the following day dried the ground out remarkably quickly and flying was resumed.

The days began to form a pattern - ground lectures on navigation theory of flight, etc, and hanging about the crew room waiting to get airborne with an instructor. My log book shows entries such as climbing, gliding, stalling, medium turns, taking off into wind, powered approach and landing, action in the event of fire, abandoning an aircraft and then, on 1 June - a great day - FIRST SOLO, 15 minutes. In fact it was my second solo, of course, but the first in Canada.

In June and into July the weather became extremely hot with, on the whole, cloudless blue skies, ideal for us sprog pilots. Visibility was superb.

The training became more intense, including such things as blind flying - just on the rather limited range of instruments - gliding approaches and landings, steep and climbing turns, side-slipping, low flying, spinning, re-starting the engine in flight, forced landings map reading, night flying and aerobatics. Much of this was with Warrant Officer Winder but also with another instructor, Sergeant Blachford, and, of course, a fair amount of solo flying. Then we progressed to solo cross-country flights, map reading to another aerodrome, landing and then returning to Neepawa.

It was during July that, on returning to Neepawa I found one of the famous a 'prairie winds' had suddenly made itself felt.

Tiger Moths were hurtling across the sky when flying with the wind and barely moving when fighting their way into it.

Flying into wind to reach the aerodrome for landing meant practically full throttle for an 80-90 mph airspeed,

giving a ground speed of only about 10-15 miles an hour.

Landing meant getting vertically over the airfield and throttling back to come almost straight down,

where if you were lucky a bunch of airmen could grab the Tiger and add their

weight to keep it on the ground.

On July 13, after reaching 27 hours solo, 26 dual, Flight Lieutenant Murgatroyd, O/C A Flight, took me up for a 50-minute final test. Four days later he gave me his assessment - a ‘Good average’ pupil pilot, ready to go on to a Service Flying Training School. A line was drawn through the Assessment Section, reading 'Any points in flying or airmanship which should be watched.' None, apparently. I was pleased.

The top pic shows two of the principal reasons for our presence at Neepawa - Tigers on the tarmac. But there was time for relaxing, I snapped Ian reading a letter from home and basking in the sun. He pictured me reading a book. We swam in a nearby lake . It was cold, despite the sun! on a 48-hour pass Ian and I hitch-hiked to Wasagaming National Park (bottom building shows entrance) and met local lasses. There was also time for horse-riding - I wasn't much good at it - and sampling home hospitality in Winnipeg.

Bottom pic: passenger-eye view of Anson on approach to runway. We went up in these twin-engined aircraft on navigation exercises. I sampled the controls. It helped me to decide I wasn't keen on twin-engined aircraft. The Anson seemed slow to respond and rather 'lumbering.'

In mid-July we awaited news of our next posting. Where to? If to a Service Flying Training School with Ansons I could have been on course for Bomber or Transport Command. If to one with single-engined Harvards then Fighter Command was in prospect.

I spoke to Sergeant Blachford 'Which do you want?' he asked. 'Harvards' I said promptly. 'Right,' he said - and I was posted to 14 SFTS at Aylmer in Ontario, by the shores of Lake Erie. So was Ian who had relatives in Toronto, Mr and Mrs Sam Booth and their daughters, Margaret and Doreen. He arranged to visit them and asked me to join him. They made me very much at home. We went dancing at somewhere called Sea Breezes, attended a wrestling match, and went swimming.

For some reason, I noted my weight - 127 lbs, or 9 stone seven lbs! Not a lot, especially when compared with my 2000 weight of 12 stone! On Sunday 2 August we reported at Aylmer was assigned to a barracks and on the following day to E Flight. We were introduced to a propped up Harvard so that we could try raising and lowering the undercarriage and get to know its cockpit design and instruments. The Harvard seemed enormous after the Tiger Moth and the mass of instruments horrifying.

The instructor true to told us that we would find it harder to play a one-string fiddle than to understand the numerous dials and switches.

On August 6, first flight, with a Flying Officer Brown, a one-hour familiarisation trip. Then more f1ights with different instructors and, on 17 August, first - for 45 minutes - solo on this what seemed very powerful aircraft.

Throughout August there was plenty of dual and solo flying, sometimes four or five flights a day, with different instructors.

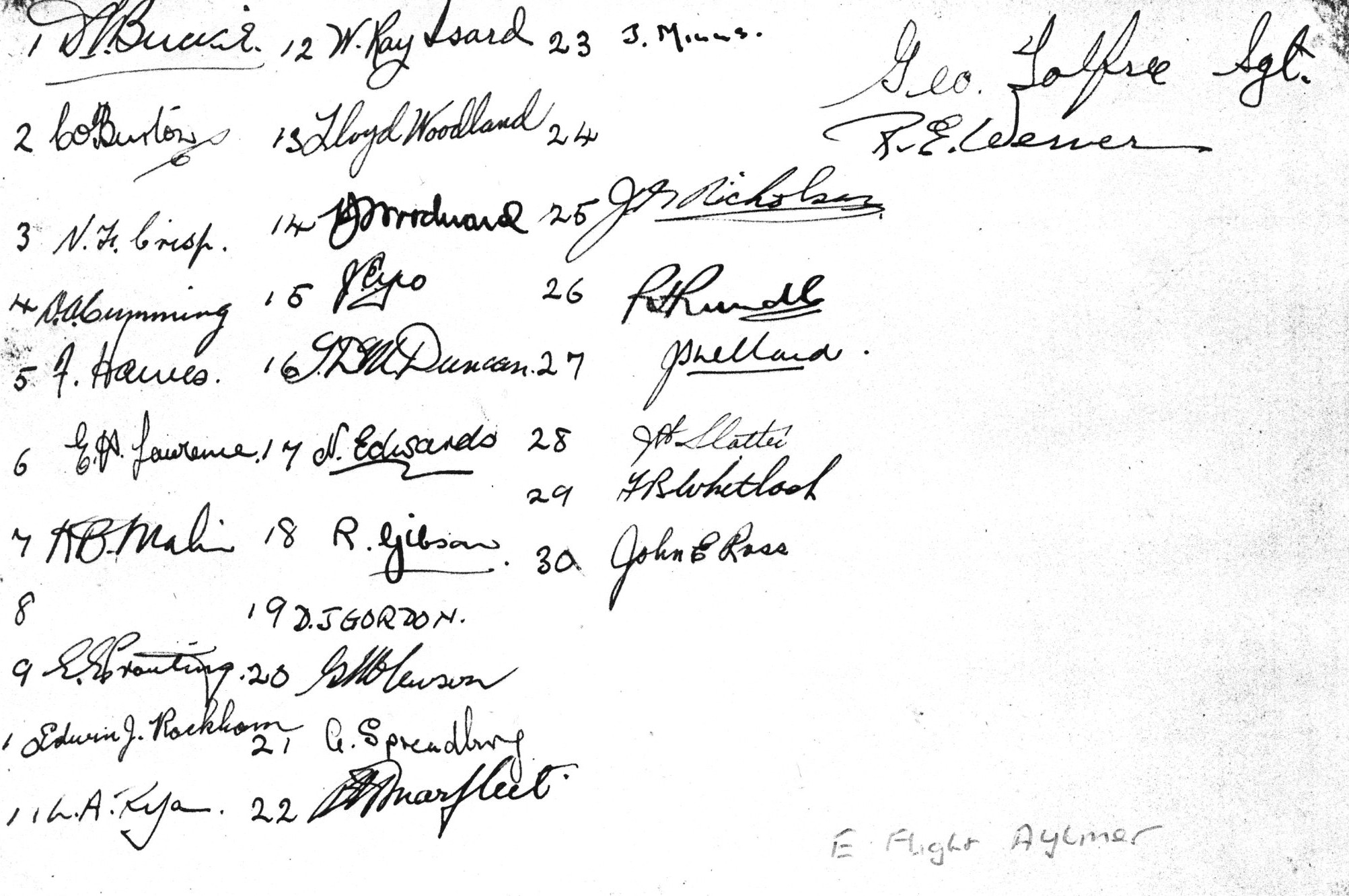

There were the usual course photographs. E flight is

the top pic, I’m number 17, with Ian number 16.

At the bottom, three photographs of Harvards, one with a Tiger parked in foreground. The barrack blocks were just the same as those at Neepawa.

In addition to staying with Ian's Toronto relatives before going to Aylmer I also stayed with them during brief leaves with Ian and also visited Detroit, crossing into the USA at Windsor, which was not far from Aylmer. In Detroit I met Charles Newman and Jeff Newman again, as they were also training not too far way.

Top four pix: Me with Mrs Booth and her mother: Ian picturing cousin Margaret with baby Beverly (with Uncle Sam just in the photograph), Ian and me with Margaret and her sister Doreen and another picture with Doreen (who was about to be married).

August 1942 was hot - so we are wearing Canadian summer weather light drill uniforms.

Two lower pix: Charles admires Detroit from a skyscraper and Detroit, showing the bridge between the USA and Canada. On the right: a young lassie I didn't know at the time but got to know very well five years later.

Charles was soon to be injured when side-slipping into the ground - which ended his flying training - and about the same time Jeff also failed as as a pilot. I lost track of them.

During one visit to Detroit I was with Jeff in a bar when an American sailor built like an all-in wrestler, came over and inquired, 'Are you Limeys?' 'I suppose so, I said. He became belligerent. 'My brudder was in England,' he said.

'He was beaten up by Limeys. Come outside.'

While I was thinking over his invitation, he turned to Jeff.

'You a Limey, too?' he asked. Jeff, who was about the same size as me, hurriedly said, 'No, no - I'm Welsh!' I expect something like this is how the term 'Welshing' came about.

The sailor turned his attention back to me. However, Jeff, who was good at pouring oil on troubled waters started commiserating with him about his 'brudder' and I joined in.

Soon we were three good friends and allies - thank goodness! At Aylmer, taking advantage of the good weather, the flying programme was intense and so was the ground instruction, taking in advanced navigation, meteorology, aerodynamics, armaments etc.

The came 17 August - a great day. I went solo in a Harvard, being up for 45 minutes, flying around locally and doing a couple of landings. I noted in my diary: 'Great to be in sole charge of this thundering, mighty Harvard.' Soon we were doing-cross country flights lasting a couple of hours or more, acrobatics, formation flying and night flying.

Other exercises, high flying, reaching 15,000 feet. It was bitterly cold up there. There was; also the Link trainer, practising turns, climbs, dives and steering compass courses in a hooded cockpit on the ground. Occasionally we flew in Yales (similar to the Harvard hut with a fixed undercarriage so a bit slower and more ponderous.

There were also some accidents, the pupil usually - but not always - being scrubbed, as we termed it.

This went on through August, September and into October. During October we sat the ground examinations.

We also had to tackle a dead reckoning navigation exercise, taking off with an instructor and then having to close a hood over the cockpit and continue only on the flying instruments. You were allowed out once to pinpoint your position and, having done so, it was back under the hood again to work out where you were in relation to where you thought you should be, calculate a wind speed from this and apply the wind and work out the courses and time to the first turning point, then the second and the third to bring you back over the aerodrome, telling the instructor when you thought you were there.

'Think I'm there,' said, thinking no such thing. 'Come out then,' he said. I pulled the hood back and looked for the 'drome. It was nowhere in sight. 'Try looking straight down,' he said. There it was, right underneath! I could hardly believe it.

Then most of us moved to a satellite airfield known as Rl, where we were told we were out of the training stage, supposed to be competent pilots. Around this time I received a letter from Tom telling me he was now a sergeant - which also told me he must be on operations.

I still have the camera I had bought in Moncton so I took it with me on a few flights. The pic is Niagara, next to it Port Bruce on Lake Erie, a view of the flat landscape, a town called Fergus, Ontario, and another Tilbury, with Lake Huron in the background, a pic of me, and at the end, approaching, Aylmer aerodrome, with its triangular runways.

On October 10, six days before my 20th birthday, I went up for what was known as a Wings check, going through umpteen manoeuvres, including aerobatics. I knew that if you pulled a Harvard round too quickly at the top of a loop it was liable to flick over. I had never flicked before, Probably a bit nervous about this important test I hauled it round too tightly - and flicked out. 'Oh dear,' I thought. 'Is that me scrubbed?'

Well no, thank goodness. I carried on, progressing to low flying formation, continuous aerobatics - and swotting away for the ground exams.

My last Harvard flight at Aylmer was on November 18. I had reached 110.30 hours solo, 100.30 dual.

On November 19 heard from Walt, trying for aircrew and passing his medical.

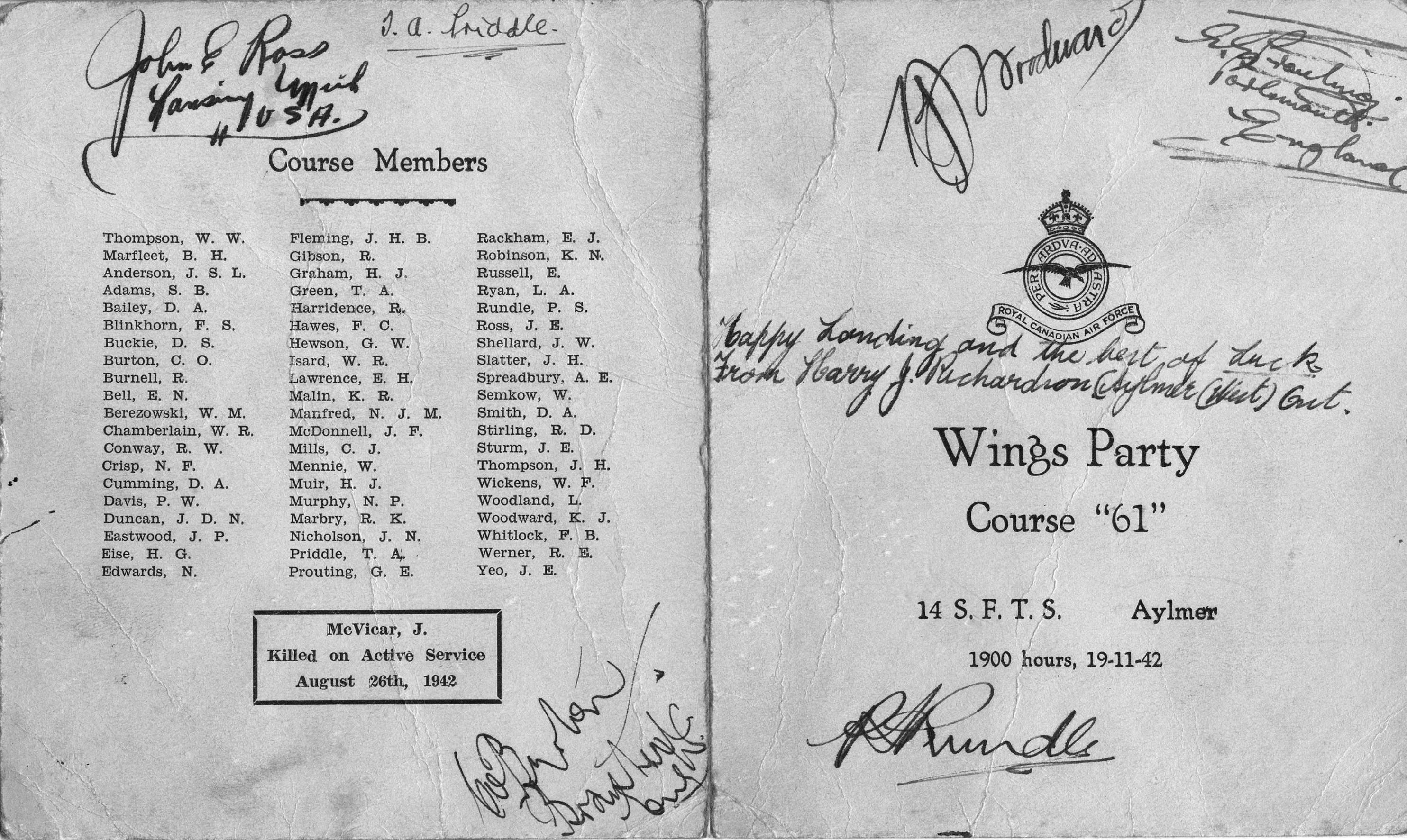

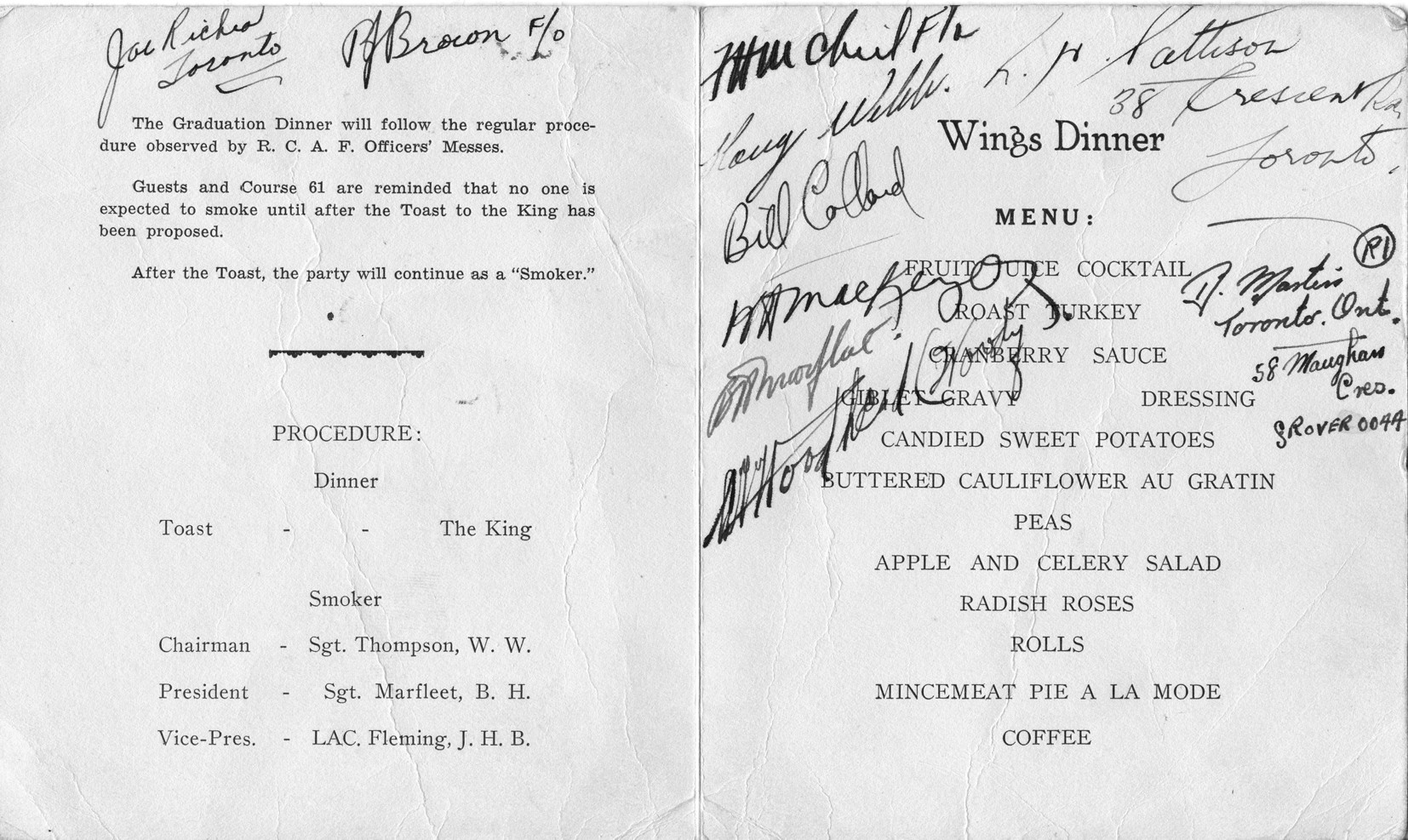

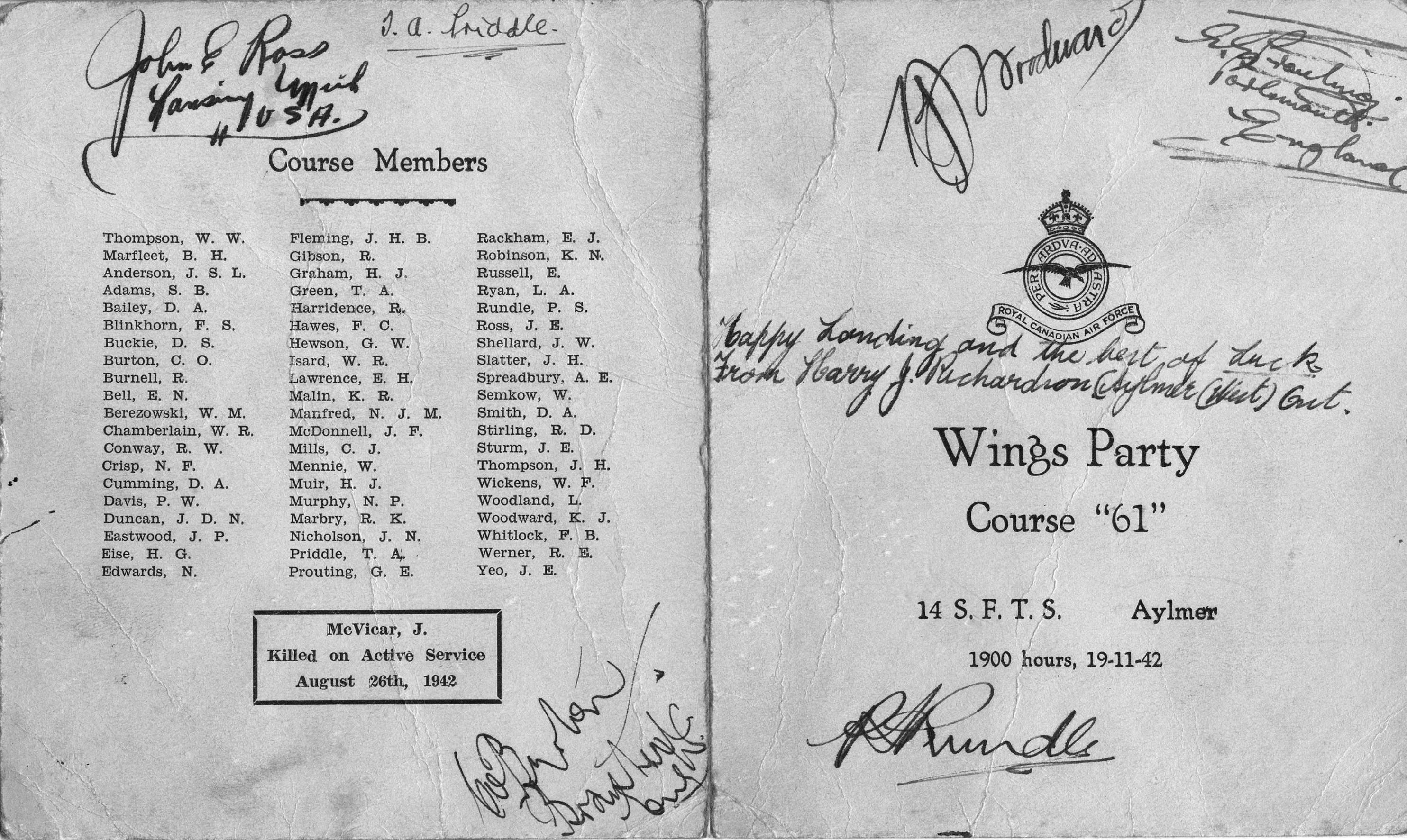

November 19 was the Wings Party - a graduation dinner, followed by what was called a 'Smoker'. On the following day the Wings Parade, when we received the pilot flying brevets. I was assessed as 'Single-engined pilot - average' and 'Pilot/navigator - average ' No points to be watched in flying or airmanship.

As no-one had said anything else, I sewed on Sergeant's tapes as well as the pilot brevet and so did Ian (top pic). We all posed for photographs. The lovely Fall weather, complete with Lake District Autumn-style leaf colours, had changed to cold and snow.

We all then set off by rail through Toronto and Montreal back to Moncton, arriving on November 25, to await the boat home.

Two days later, while on parade in the Drill Hall, my name was called out. I wondered what I had done wrong. I was told to get rid of the Sergeant stripes - I had been commissioned as a Pilot Officer.

I moved to the Officer's Quarters, rushed out in a snow-storm to get a uniform from Eaton's department store, had to accept the nearest to what might be called a fit. It had Royal Canadian Air Force buttons, which was to get me into trouble later - and, on December 11, left Moncton by rail for Halifax to board the 'Queen Elizabeth' at 10 pm. We sailed for Gourock on December 13.

The Clyde-built 'Queen Mary' and 'Queen Elizabeth' sailed backwards and forwards across the Atlantic without escort throughout the war, relying on speed for safety. Each could do 30 knots.

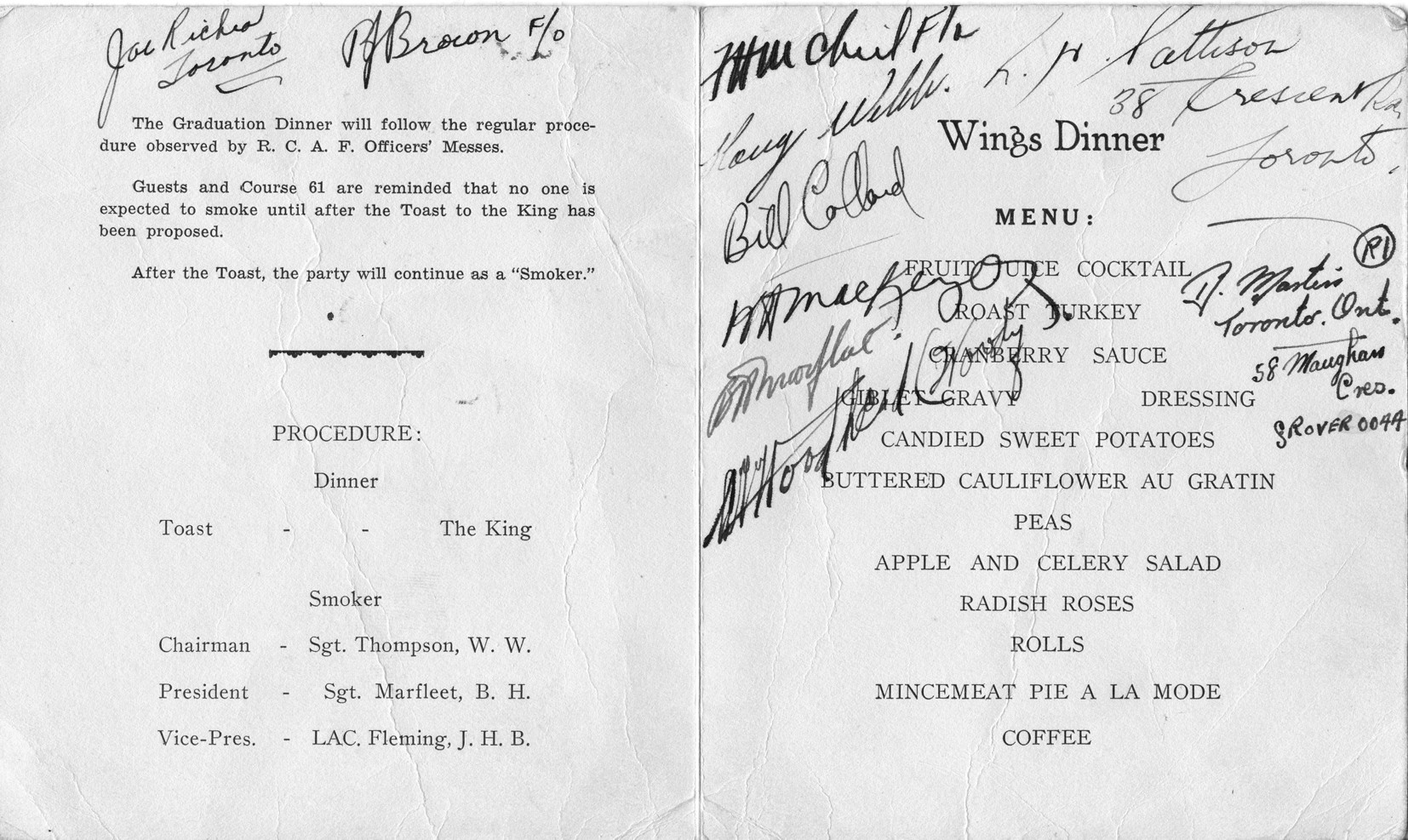

Before continuing with the return voyage, thought it might be nice to include in this history a copy of the 14 Service Flying Training School invitation and menu for the Course 61 Wings Party graduation dinner, held on 19 November 1942 at Aylmer. All course members were listed on the back page, although they did get one of Ian's initials wrong. He was J D M, not N.

The menu was splendid - and we were served by the officers. I collected a few autographs.

We were also presented with a book picturing famous Canadian World War 1 aces, such as Bishop and Mannock. It was inscribed by the Group Captain: 'Congratulations, Edwards. May you be even greater than these!'

Will include the book - if I can find it!

Returning to the 'Queen Elizabeth', we soon discovered it was a super-duper troopship. There were so many on board that although they were serving meals all day long, each of us only got two meals a day. the times depending on the rota. I was lucky - breakfast was mid-morning and the other meal late afternoon. The family will no doubt recall that Beth, aged about 8, saw the start of the maiden voyage of the Queen Mary, which was launched at Clydebank in September 1934 and made its maiden voyage some months later, sometime in early 1935. She also carried thousands of on each voyage throughout the war.

The 'Queen Elizabeth', also Clyde-built, was not launched until five years later, in 1940. Instead of being fitted out as a luxury liner she was equipped as a troopship, carrying as many as possible. The bunks were four-tier! You had to stretch out horizontally to get on your bunk.

Nor was she fitted with stabilisers, with the result that as she whizzed across the Atlantic, avoiding submarines by sheer speed, she rolled heavily most of the time and very heavily indeed in rough seas. In your bunk you slid from head to toe and back again. In the lounge you were thrown backwards and forwards in your chair, which was fastened down.

We didn't mind - far better than being caught by U-boats.

After five days at sea we were within range of German spotter aircraft so were told to sleep in our clothes and were not allowed on deck. After six days, land came into sight and that same night we anchored in Gourock. The voyage had taken six days. On the 'Batory' it had taken eight.

The 'Queen Elizabeth' was to feature later in my life, when I was PR consultant to Manchester Liners.